Summary

George H. Blackford © 2009, last updated 5/1/2014

Part I: Conservative Economic Policies

Part I examines how changes in economic policy over the past forty years have affected the economic system and explains how these policy changes have affected the way in which our economic system functions.

Chapter 1: Income, Fraud, Corruption, and Efficiency discusses the way in which deregulation and the change in attitude toward regulating economic behavior has led to a rise in fraud and corruption within our economic and political systems, and how this increase in fraud and corruption has, in turn, led to a loss in economic efficiency through the creation of speculative bubbles and an inequitable distribution of income derived from speculative rather than productive endeavors.

Chapter 2: International Finance and Trade discusses how deregulation in the area of international finance has led to international financial crises that have necessitated government bailouts of our financial institutions to keep them from failing. The way in which this change in policy has led to an overvalued dollar that has wrought havoc with the American economy as it devastated our manufacturing industries and transformed the United States from the largest creditor nation in the world to the largest debtor nation in the world is also discussed. The Appendix at the end of this chapter provides a primer on the way in which international exchange rates are determined and how these rates affect economic interactions between countries.

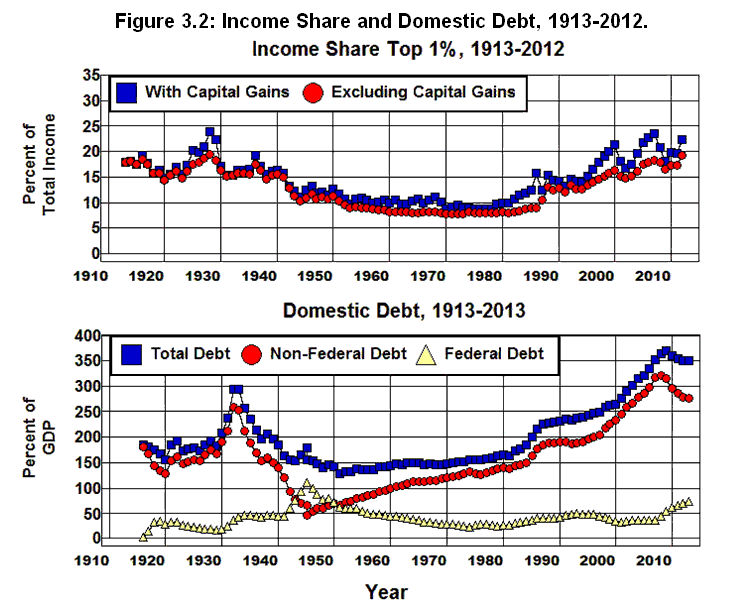

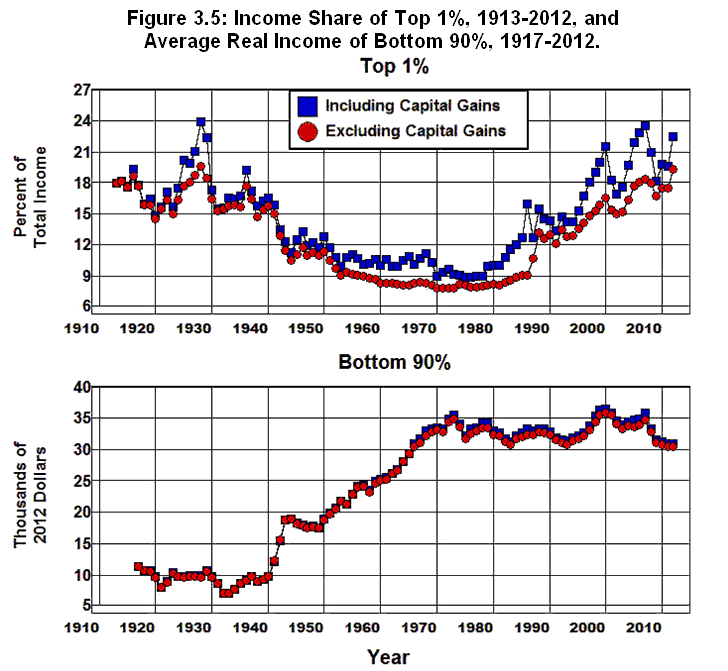

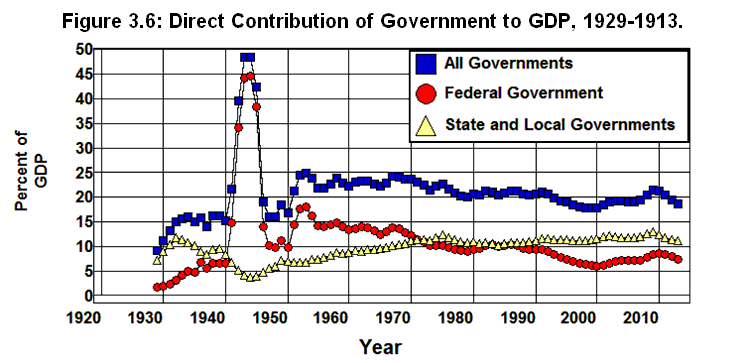

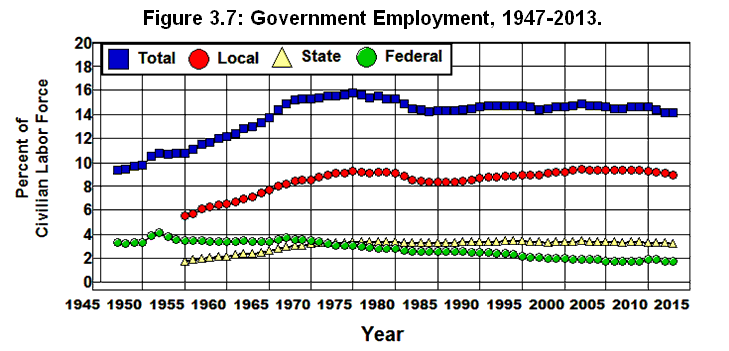

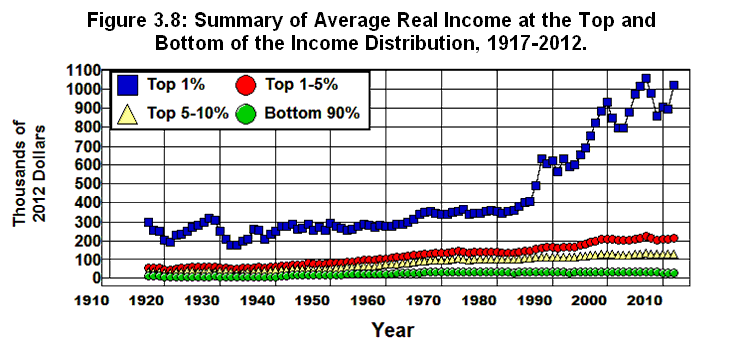

Chapter 3: Mass Production, Income, Exports, and Debt examines the relationship between mass-production technology, the distribution of income, exports, and debt within the economic system. It is argued that in order to be economically viable, mass production techniques require mass markets—that is, markets with large numbers of people who have purchasing power—otherwise, the mass quantities of goods and services that can be produced via mass-production techniques cannot be sold. The viability of mass markets within a society, in turn, depends on the distribution of income in that the distribution of income limits the extent to which domestic mass markets can be sustained without an increase in debt relative to income: The less concentrated the distribution of income, the larger the domestic mass market that can be sustained; the more concentrated the distribution of income, the smaller the domestic mass markets that can be sustained.

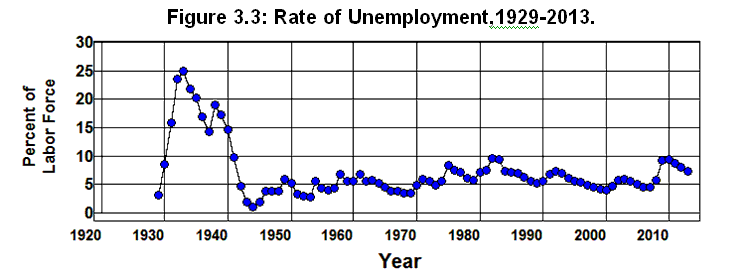

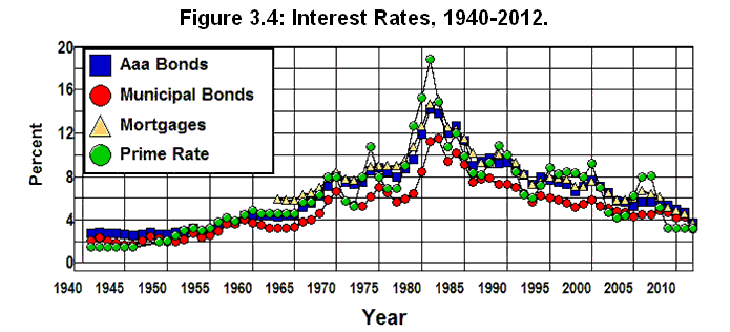

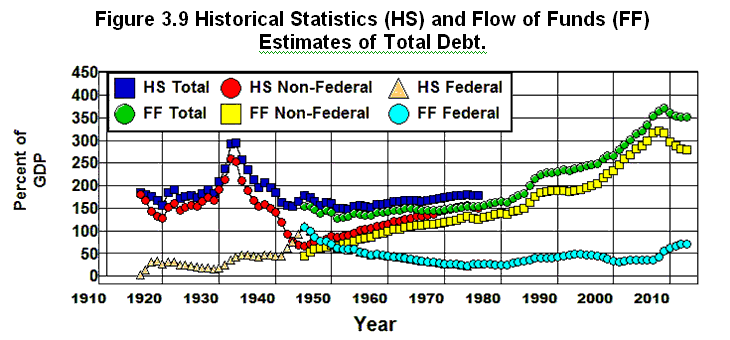

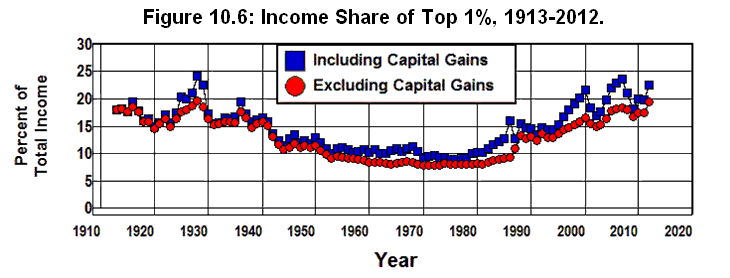

It is also argued that, in a mass production economy, the mass markets needed to obtain full employment can only be maintained in the face of an increasing concentration of income if there is an increase in debt relative to income. It is further argued that the process by which debt must be increased in this situation is unsustainable. As debt increases relative to income the strain on the financial system must grow, and, eventually, a financial crisis must result as the ability to service the growing debt falters. Hence, the financial crisis of 1929-1933 following the increase in debt and the concentration of income in the 1920s, the savings and loan crisis of 1987-1991 following the increase in debt and the concentration of income in the 1980s, and the current financial crisis following the increase in debt and the concentration of income in the 2000s.

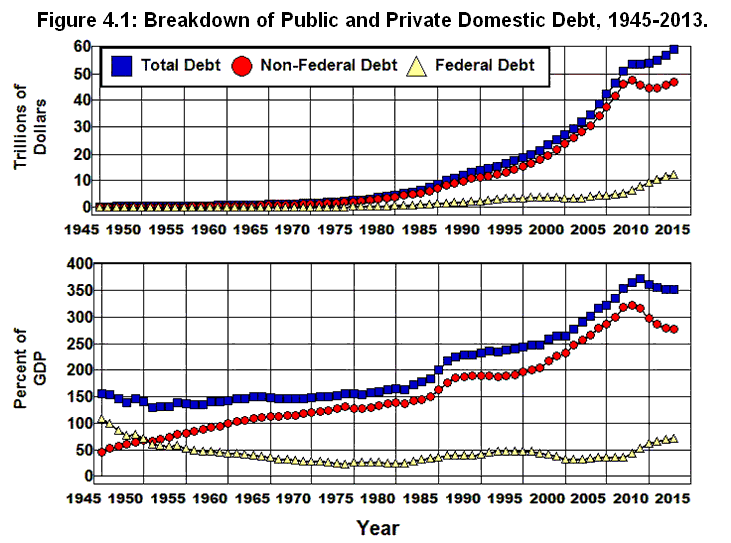

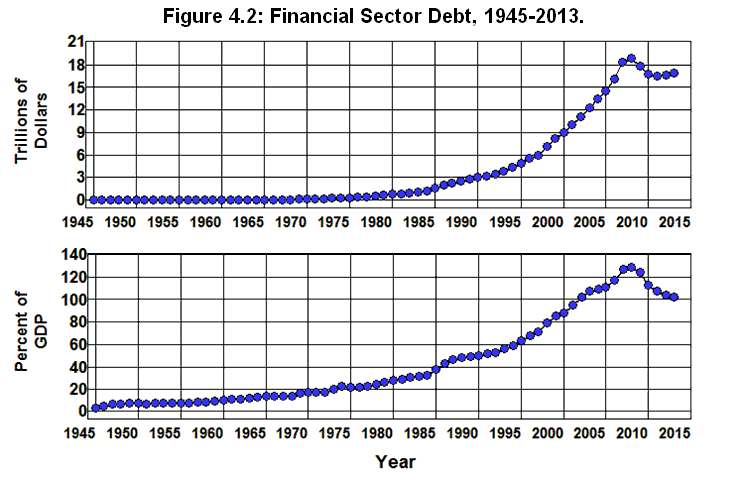

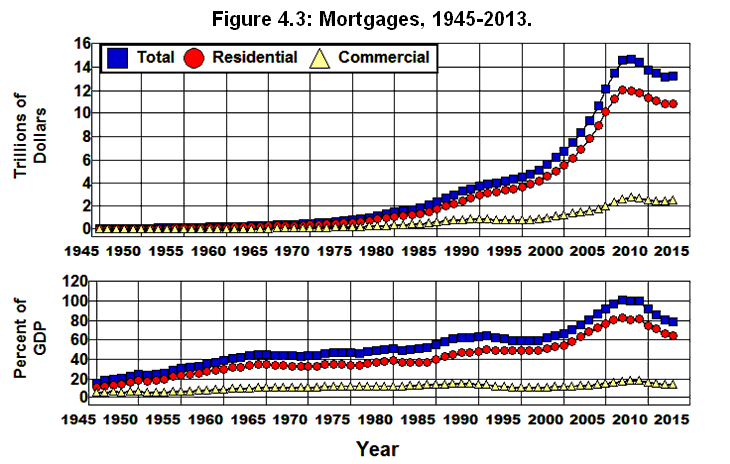

Chapter 4: Going into Debt examines the relationship between the deregulation of our financial system and the rise of domestic debt from 1970 through 2010. The way in which financial institutions create debt through the process of financial intermediation is explained, and it is argued that there are powerful incentive within the financial system that lead financial institutions to fund speculative bubbles that increase debt beyond any possibility of repayment. When this occurs a financial crisis that brings down the economic system is inevitable. It is further argued that not only is this what happened during the housing bubble in the 2000s, it is also what happened during the real estate and stock-market bubbles of the 1920s, and the parallels between the between the 2000s and the 1920s are examined.

Part II: Financial Instability and the Crash of 2008

Part II explains how our financial system works and how the changes in economic policy that have occurred over the past forty years led to the economic catastrophe we are in the midst of today.

Chapter 5: Nineteenth Century Financial Crises gives a brief history of our financial system as it evolved during the nineteenth century. The way in which financial institutions—specifically, banks but any financial institution that finances long-term assets through short-term debt must be included here—differ from other businesses is examined.

The fundamental liquidity and solvency problems that are unique to banks are explained along with the way in which increasing leverage within the financial system leads to financial crises that cause economic instability. The fundamental mechanism by which banks create debt—namely, by virtue of the fact that banks are able to increase the amount of money they can borrow from the non-bank public by increasing the amount of money they lend to the non-bank public—is explained in this chapter.

The implications of the fundamental problems endemic in the banking system with regard to economic instability are examined as well as the failings of the nineteenth century banking systems that led to financial crises.

Chapter 6: The Federal Reserve and Financial Regulation explains the way in which our modern financial system is structured by the Federal Reserve. How the Federal Reserve determines the amount of currency that is available to the economic system is explained as well as how the interaction between the banking system and the non-bank public—given the amount of currency that is made available by the Federal Reserve—determines the amount of debt created by the banking system as the banking system increases the amount it can borrow by increasing the amount it lends.

The way in which the Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s led to a change in attitude toward the nineteenth century ideological dictates of free-market capitalism is also examined in this chapter. It is argued that the resulting change from an ideological to a pragmatic view of the economic system led to the creation of a comprehensive system of financial regulation in the 1930s through the 1960s that served our country well until we began to dismantled this system in the 1970s.

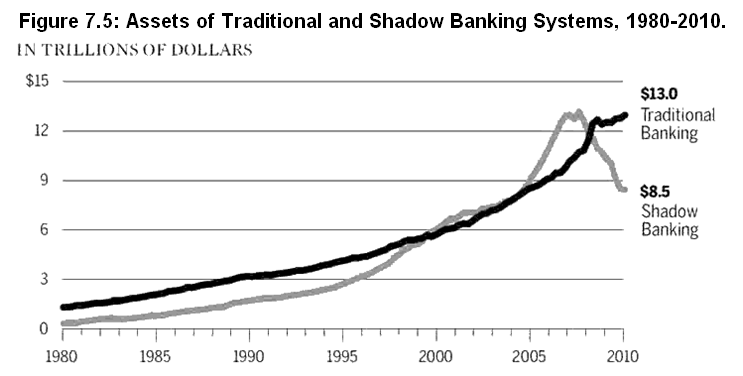

Chapter 7: Rise of the Shadow Banking System examines the process by which the pragmatic system of financial regulation created in the wake of the Great Depression was dismantled as the failed, nineteenth-century ideology of free-market capitalism began to gain favor again among policy makers in the 1970s.

The basics of financial markets and the nature of financial instruments are explained along with the changes in the financial system that came about through the creation of markets for collateralized debt instruments. It is shown how the change in attitude toward regulation, combined with the creation of markets for collateralized debt instruments, led to the rise of financial institutions—shadow banks—that operated outside the purview of the financial regulatory system and yet operated like banks in that they held long-term assets financed by short-term debt.

The way in which the shadow banks pose all of the treats to economic stability that an unregulated banking system poses is examined, and it is argued that since the shadow banks were allowed to operate outside the purview of the regulatory system, there was nothing to keep them from reverting to the kinds of behaviors that led to the kinds of crisis we experienced during the era of unregulated finance that culminated in the Crash of 1929 and drove us into the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Chapter 8: LTCM and the Panic on 1998 examines the first major financial crisis caused by a shadow bank: the worldwide panic that resulted from the near failure of a single hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), in 1998.

It is shown that all of the problems endemic in the failure to regulate the shadow banking system—problems that subsequently led to the financial crisis we are in the midst of today—were acknowledged in the government reports on this crisis submitted by the President's Working Group and by the General Accounting Office.

It is further argued that ideological blindness on the part of policy makers in the Clinton administration and the Republican congress at the time made it impossible for those in charge of our government to even see the extent of the threat these problems posed let alone to follow the recommendations of the General Accounting Office and bring shadow banks under the purview of the regulatory system.

Chapter 9: Securitization, Derivatives, and Leverage explains the basics of the securitization process, the nature of financial derivatives, and the way in which financial derivatives increase leverage and, hence, risk within the financial system.

How Mortgage Backed Securities (MBSs) come into being is also explained in this chapter along with Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs), Credit Default Swaps, synthetic CDOs, and options and futures contracts.

The risks involved in trading financial derivative in over-the-counter markets as opposed to trading these kinds of financial instruments on exchanges with the protections provided by a clearinghouse are explained as well, and the reasons why the failure to regulate the markets for financial derivatives had such devastating consequences when the crisis began in 2007 are examined.

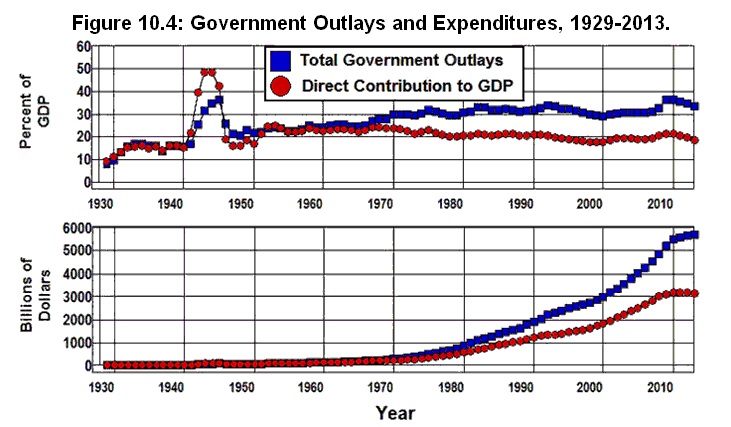

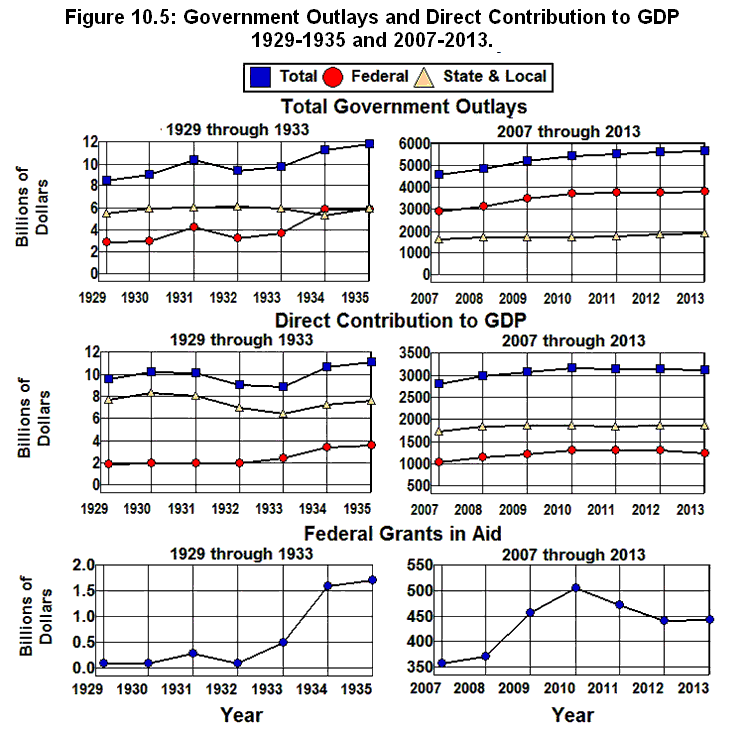

Chapter 10: The Crash of 2008 chronicles the events that led up to the Crash of 2008 and the way in which we dealt with the economic catastrophe that followed. It is argued that because of the extent to which debt was allowed to accumulate, and the extent to which the unregulated markets for over-the-counter derivatives were able to increase risk in the financial system, the financial situation we faced in 2008 was far worse than anything we faced in 1929.

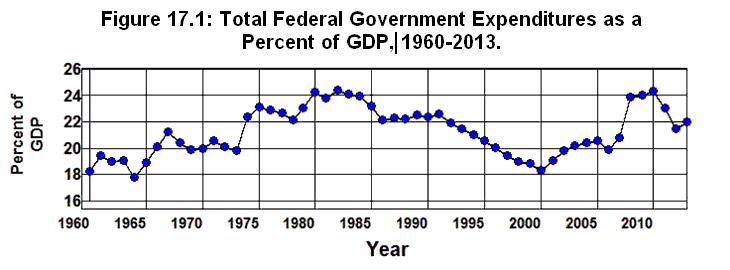

It is further argued that there are but three threads by which the economy is hanging today that have made it possible for us to avoid, so far at least, the disastrous consequences that followed the Crash of 1929, and that these three threads are there only because of the size of our federal government. These three threads are 1) the heroic actions of the Federal Reserve in keeping the world's financial system from collapsing, 2) the size and stability of federal government expenditures that placed a break on the downward spiral of income and output that was initiated by the crash in 2008, and 3) the existence of our social-insurance programs that have mitigated the kind of human misery and suffering that, in the absence of these kinds of programs, inevitably accompany the kind of economic catastrophe we are in the midst of today.

Finally, it is argued that the free-market ideologues—whose mantra of lower taxes, less government, and deregulation brought on the economic crisis we are in the midst of today—are doing everything they can to cut the three threads by which our economic system is hanging, and in this Alice-in-Wonderland world in which we live there is every reason to believe they are going to do this if and when they regain control of the federal government.

Part III: The Federal Budget

Part III examines the history of the national debt, the federal budget, and our social-insurance programs in an attempt to sort through the sophistry endemic in the debate surrounding these entities. All of the data in these chapters are taken from the official statistics published in the Office of Management and Budget's Historical Tables or from other official government documents.

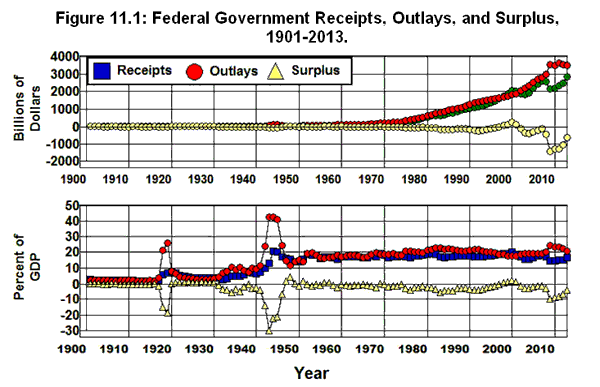

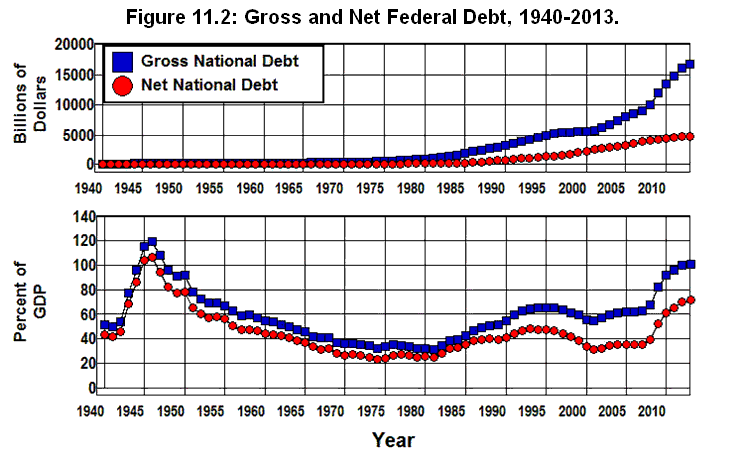

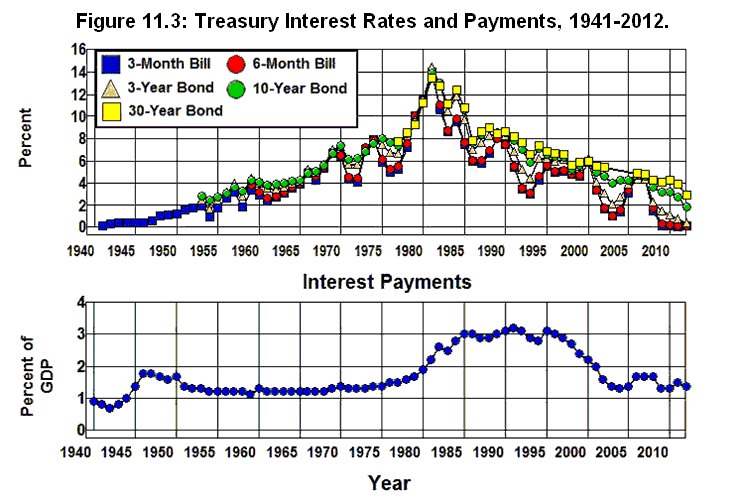

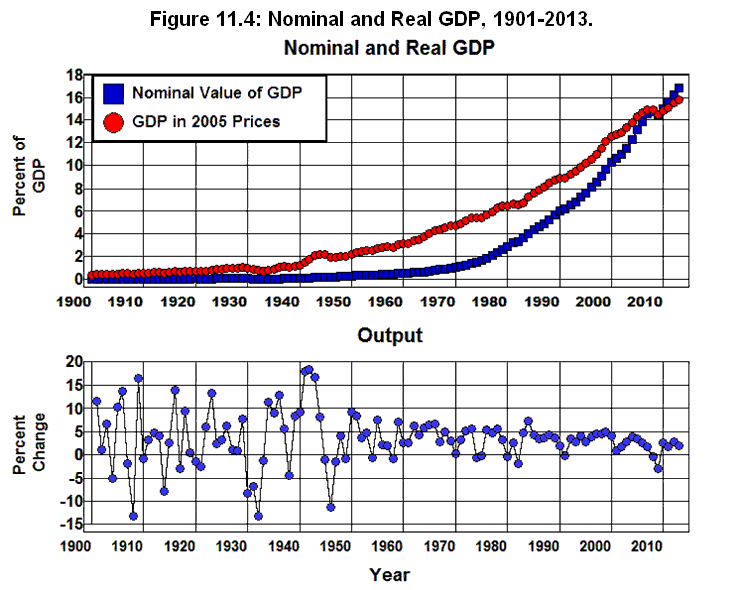

Chapter 11: History of the National Debt begins by explaining a number of definitions and relationships—such as definitions of gross and net national debt and the relationship between the national debt and surpluses and deficits in the federal budget—that are required to understand what the national debt is and where it comes from. The importance of measuring the national debt relative to some other variable in the economic system, such as GDP, is explained.

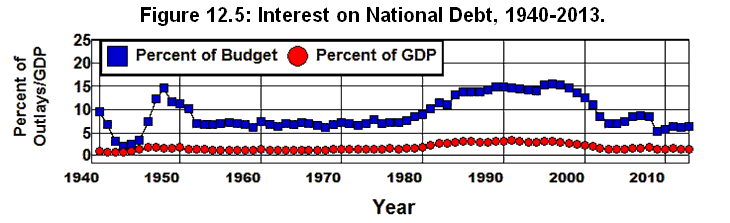

The history of the national debt is examined for the 83 years between 1929 and 2012. The basic conclusions that result are that the primary sources of the national debt are 1) increases in defense expenditures associated with war, 2) economic downturns associated with recessions and depressions, and 3) cutting taxes in the face of rising government expenditures. These conclusions are reinforced when we look at the history of the federal budget in the next chapter.

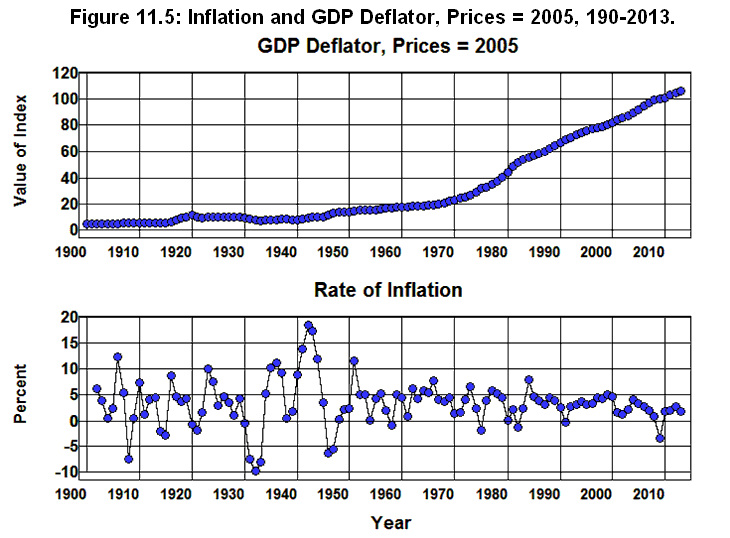

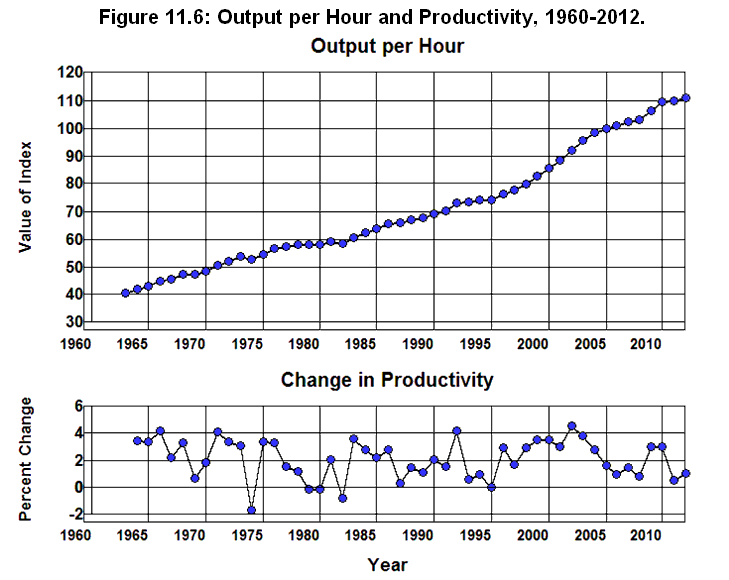

A number of technical issues surrounding the construction of aggregate measures of economic activity—such as measures of total output, the average price level, and the level of productivity in the economy—are explained in the appendix at the end of this chapter.

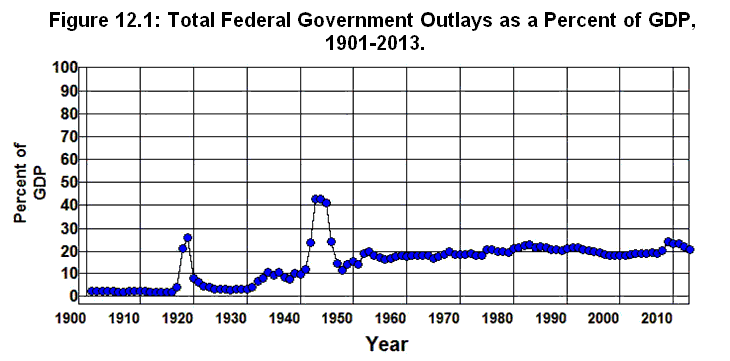

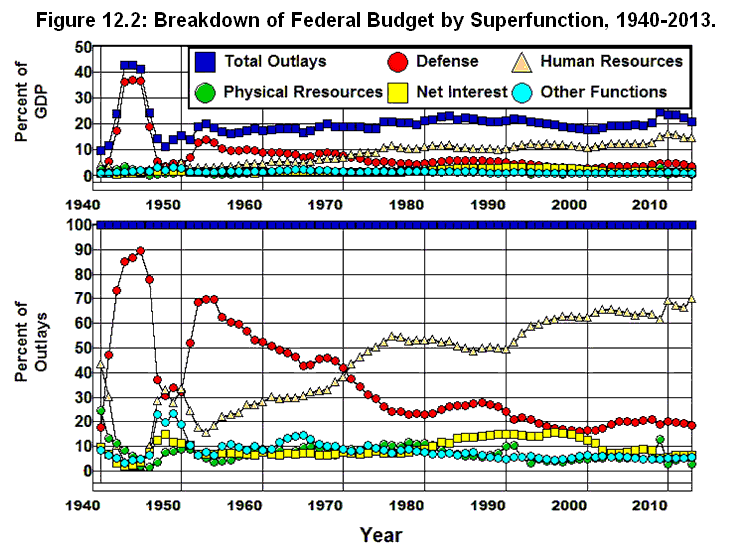

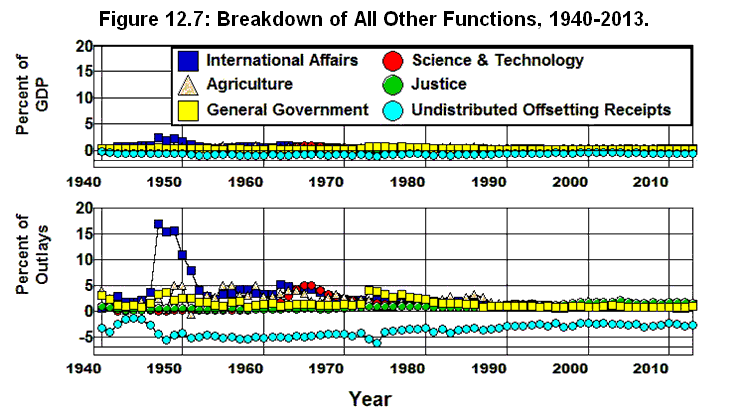

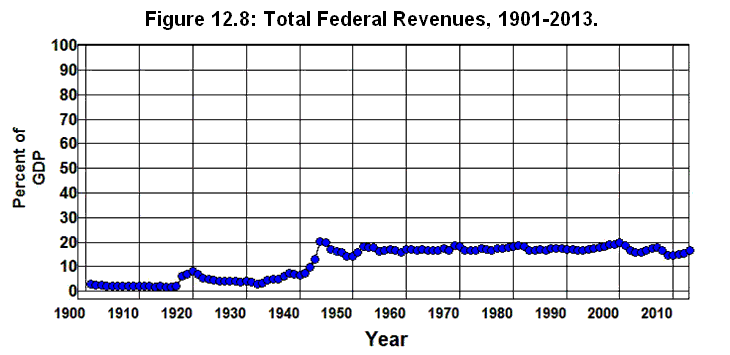

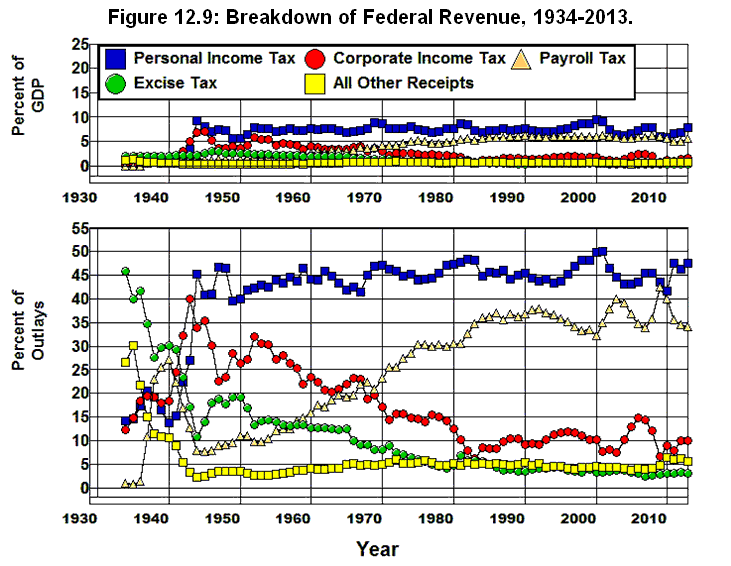

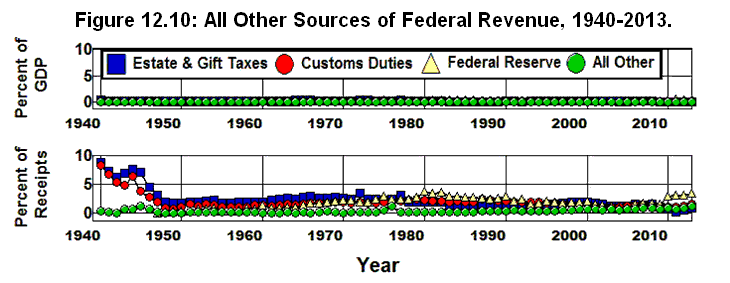

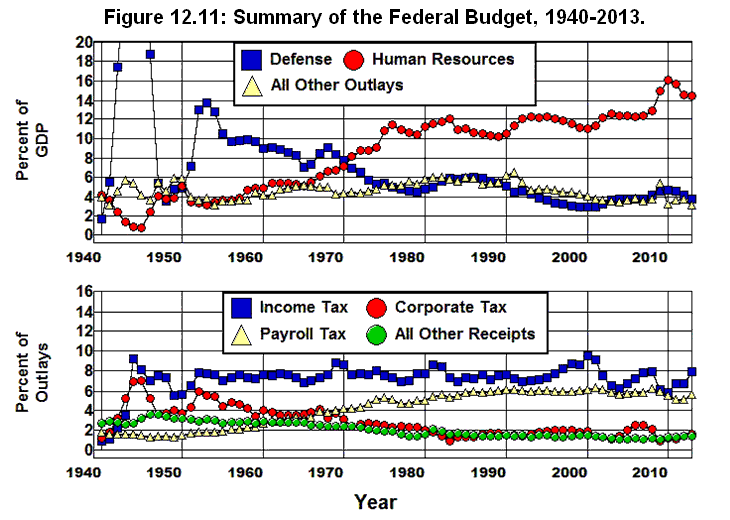

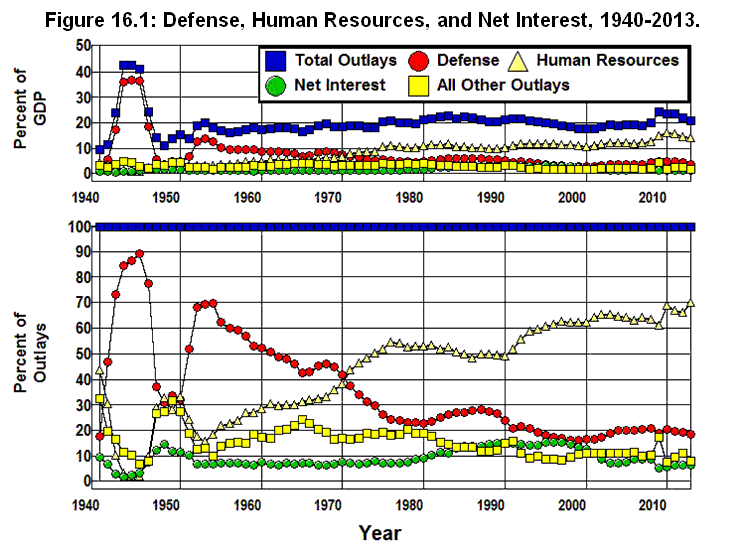

Chapter 12: History of the Federal Budget examines the history of the federal budget from the perspective of how our country has changed since 1929. All of the major categories of the federal budget are plotted in this chapter from 1940 through 2012.

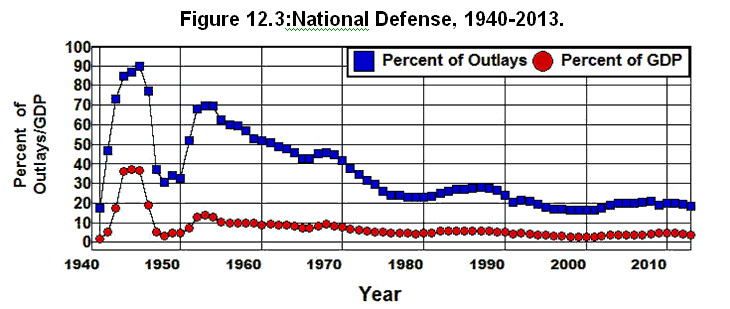

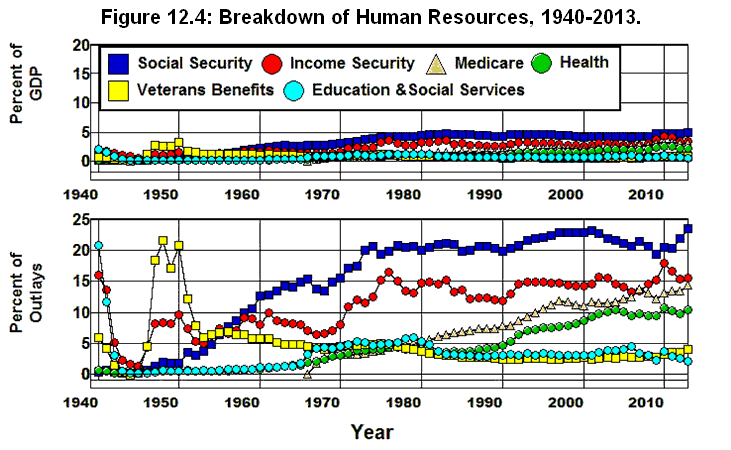

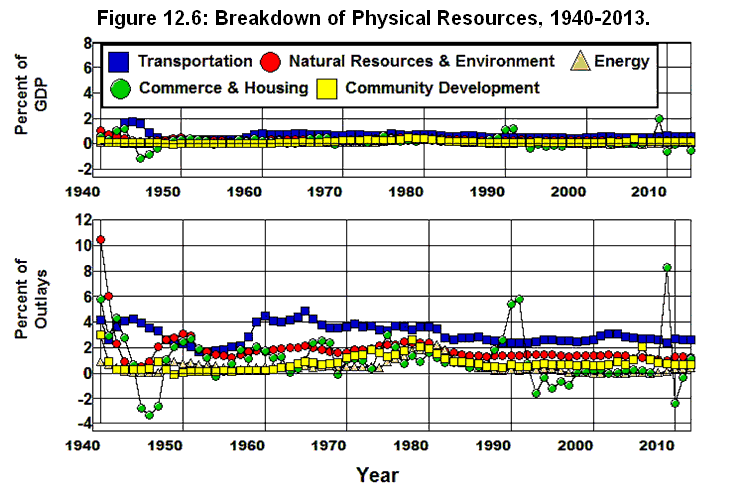

It is argued that the loss of faith in free-market capitalism brought on by the Great Depression and our international interventionist policies brought on by World War II and the ensuing Cold War had profound effects on the American psyche that led to dramatic changes in the federal budget following 1929. In looking at the history of the budget we find that these factors led to a dramatic increase in the size of the budget relative to the economy in the 1930s through the 1950s, and that this increase was dominated in the 1940s by an increase in defense expenditures. We also find that while the size of the federal budget relative to the economy has been relatively constant since the 1960s, the composition of the budget has changed dramatically. The most dramatic change has been the decrease in the fraction of the budget that is devoted to defense and the increase in the fraction that is devoted to Human Resources—that is, devoted to the social-insurance programs that came out of Roosevelt's New Deal, the most important of which are Social Security and Medicare.

The primary mechanisms by which the increase in the Human Resources component of the budget has been financed over the past 60 years is seen to have been a decrease in expenditures on national defense and an increase payroll taxes as a percent of GDP. This decrease in national defense and increase in payroll taxes was used to finance a reduction of all other taxes collected by the federal government as well. The reduction of taxes on corporations has been especially dramatic in this regard.

Finally, it is argued that if we are to have less government the place we have to cut the budget is in the Human Resources portion of the budget and possibly defense since virtually everything else has been cut to the bone since 1980.

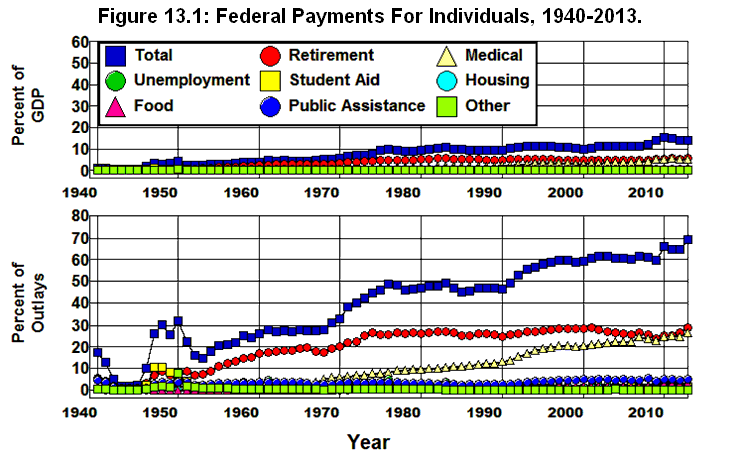

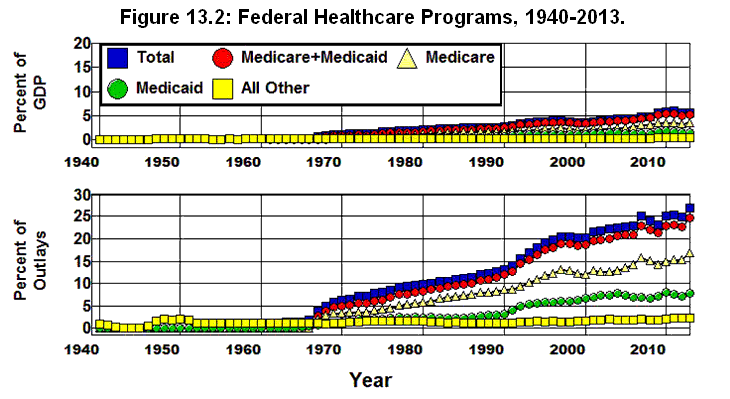

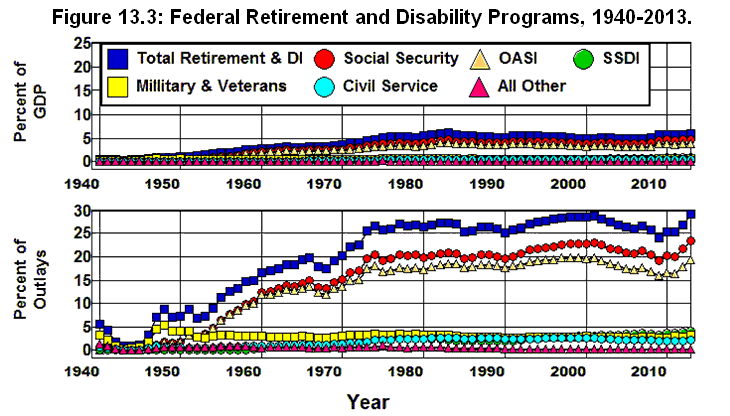

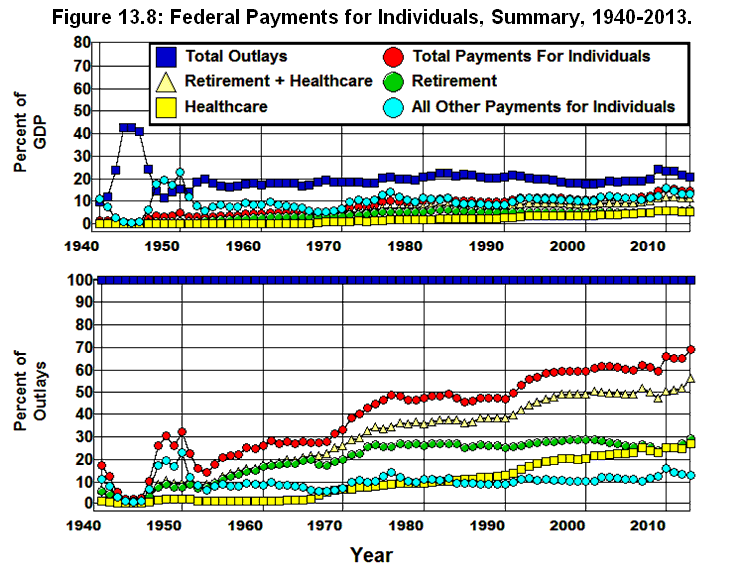

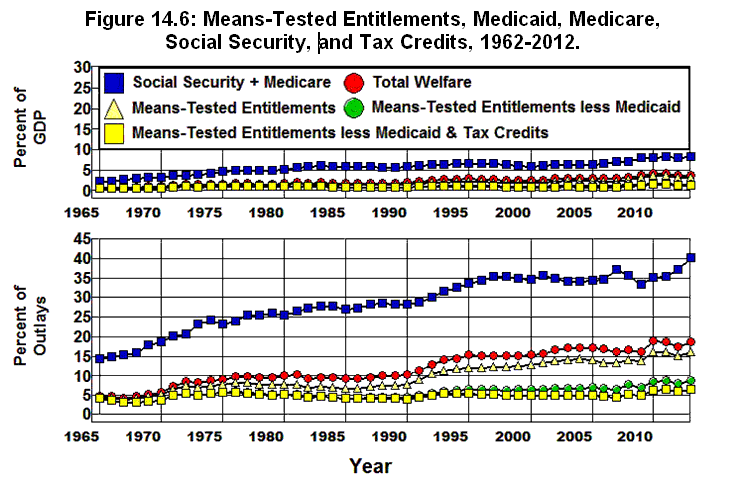

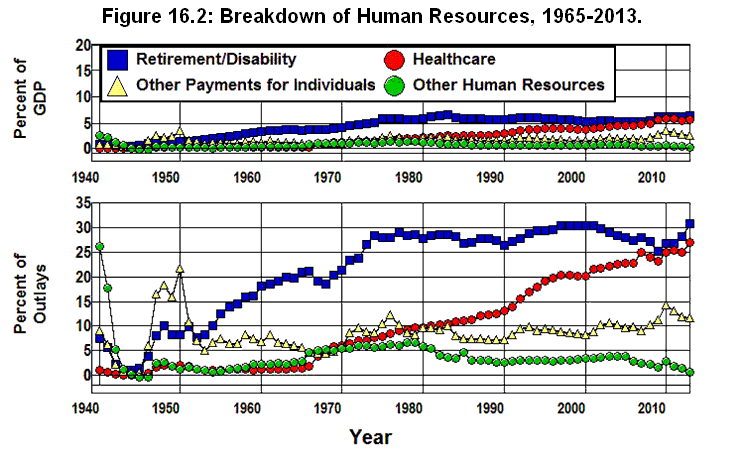

Chapter 13: Human Resources and Social-Insurance examines the portion of the federal budget devoted to the social-insurance programs (Human Recourses) that have grown out of Roosevelt's New Deal. This category of the budget has gone from 33.4% of the budget and 4.6% of GDP in 1950 to 64.4% of the budget and 12.7% of GDP in 2007. The great bulk of the expenditures in this category fund our social-insurance programs.

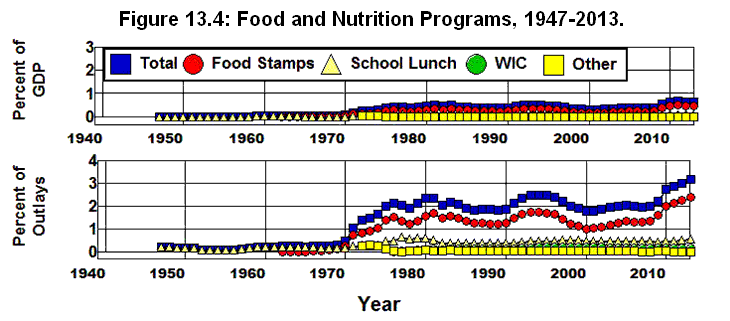

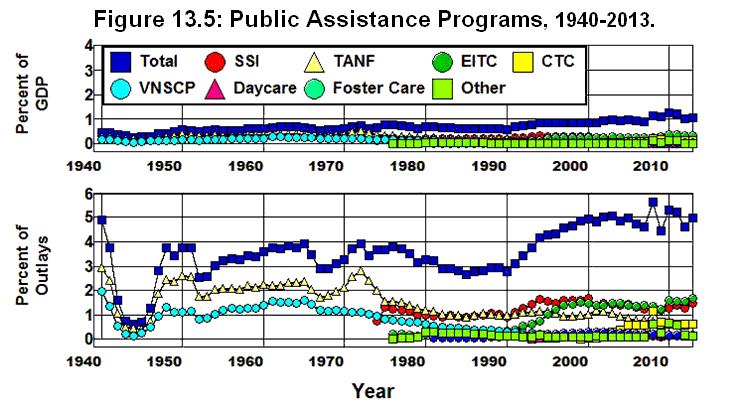

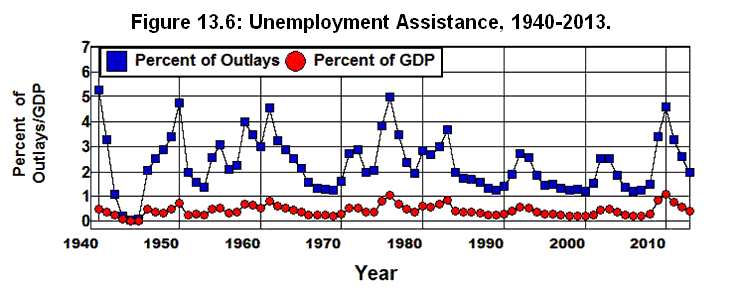

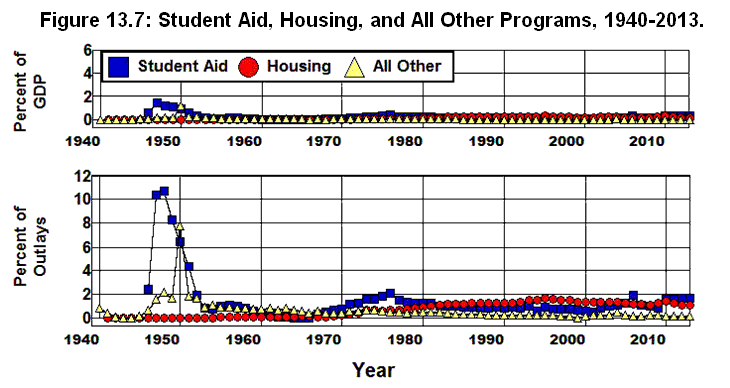

We find that Human Resources is dominated by federal healthcare and retirement programs and that Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security dominate these programs. Healthcare and retirement went from 0.0% and 5% of the budget in 1940 to 25% and 26% of the budget in 2007, respectively. All other categories of Human Resources were less than 5% of the budget during the entire period. In terms of GDP, healthcare and retirement grew to 4.9% and 5.2% of the economy by 2007 while none of the other categories in Human Resources exceeded 1% of the economy during that period save unemployment compensation which hit 1.1% of GDP in 1976 following the 1973-1975 recession.

When we examine the data we find that 71% of the increase in the total costs of Human Resources programs since 1965 can be attributed to the increase in the cost of healthcare, 21% to the increase in the cost of federal retirement programs, less than 6% by the increase in the cost of federal non-healthcare, public assistance programs, and less than 3% by the increases in the cost of all other Human Resource programs combined.

Chapter 14: Welfare, Tax Expenditures, and Redistribution examines the welfare programs in the federal budget, that is, those programs the benefits of which are available to aid the poor and are specifically designed to redistribute income from those who are better off to those who are less fortunate.

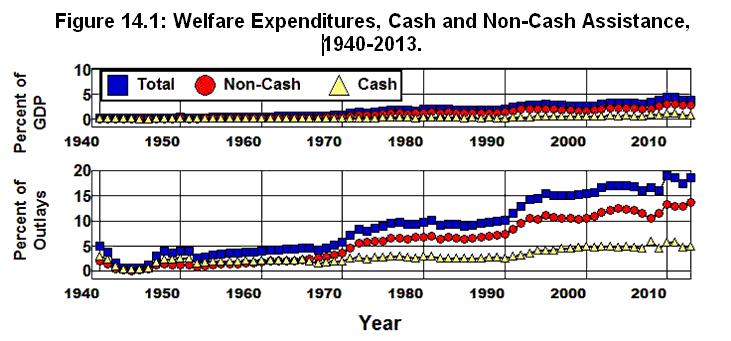

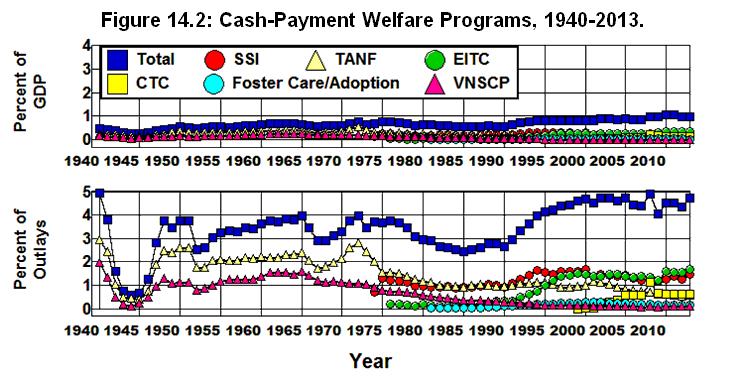

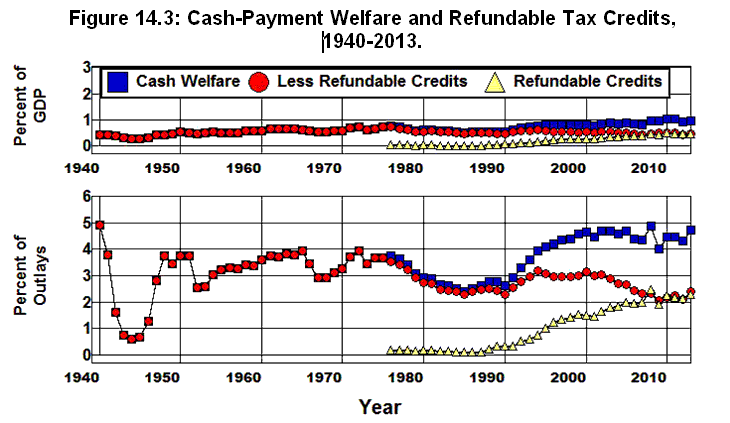

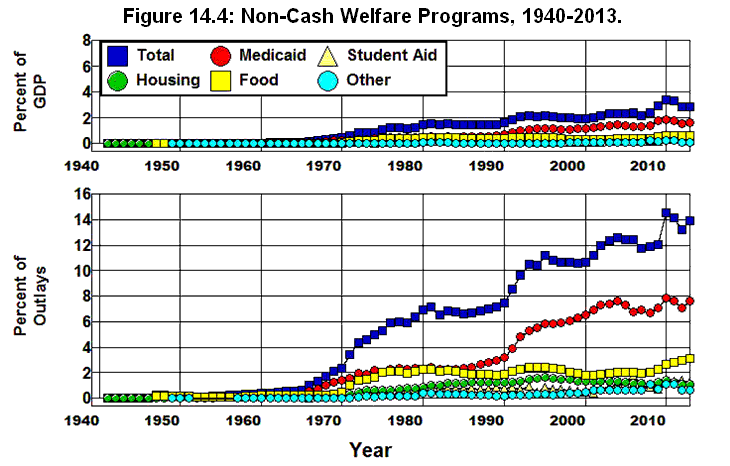

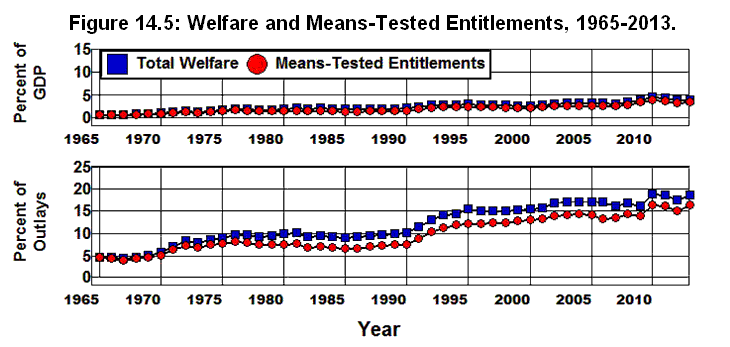

We find that total welfare expenditures grew gradually from 1952 through1967 and then increased dramatically from 4.3% of the budget and 0.85% of GDP in 1967 to 16.3% of the budget and 3.2% of GDP in 2007. When we break these expenditures down into cash and non-cash benefits we find that expenditures on cash-benefit welfare programs relative to the economy and federal budget in 2007 was essentially the same as it was in 1965, less than 5% of the budget. We also find that while virtually all of the cash-benefit welfare payments went to people who were not employed in 1965, fully half of the cash-payment welfare expenditures went to the working poor in 2007, rather than to recipients who were not employed.

We also find that expenditures on non-cash assistance programs represented 73% of welfare expenditures in 2007 and only 27% of the welfare expenditures were cash benefit programs. At the same time, we find that the Medicaid program amounted to 7.0% of the budget in 2007 and, thus, accounted for 42% of all welfare expenditures in 2007 and 56% of all expenditures on non-cash assistance programs. None of the other welfare programs exceeded 2% of the budget in 2007 or 0.4% of our gross income. The single most important factor in driving up the cost of welfare since 1967 is to be found in the Medicaid program.

In addition to welfare expenditures, there were over 200 provisions in the federal tax code in 2007 that had the effect of redistributing income within our society. These provisions are referred to as tax expenditures, and since the benefits of tax expenditures are guaranteed by law to all who qualify for them, they are, in fact, entitlement programs.

In examining the various categories of tax expenditure entitlements in the federal budget we find that the extent to which tax expenditures redistribute income from the general tax payer to upper income groups far exceeds the extent to which welfare programs redistribute income from the general tax payer to lower income groups.

Part IV: Coming to Grips with Reality

Part IV examines the major economic problems with which we are faced today, the way in which we should deal with these problems, and the role played by ideology in creating these problems and in preventing solutions to these problems.

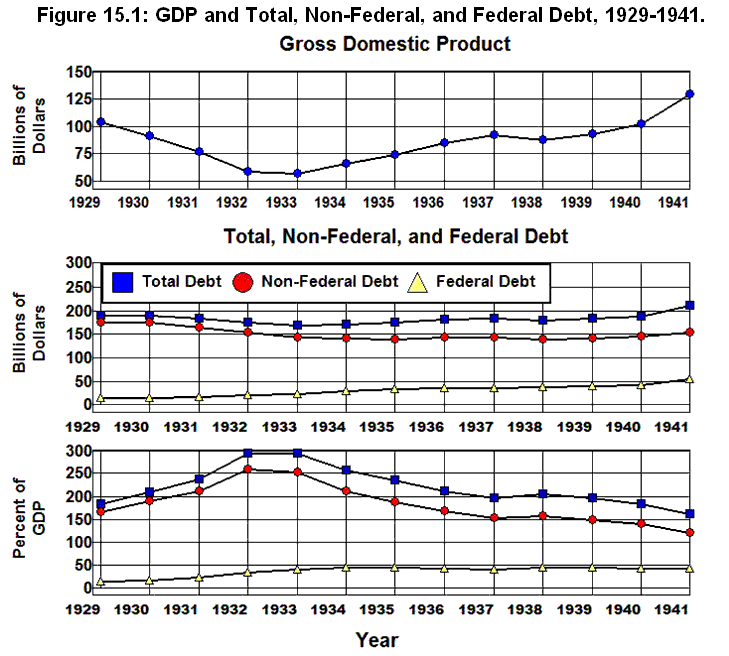

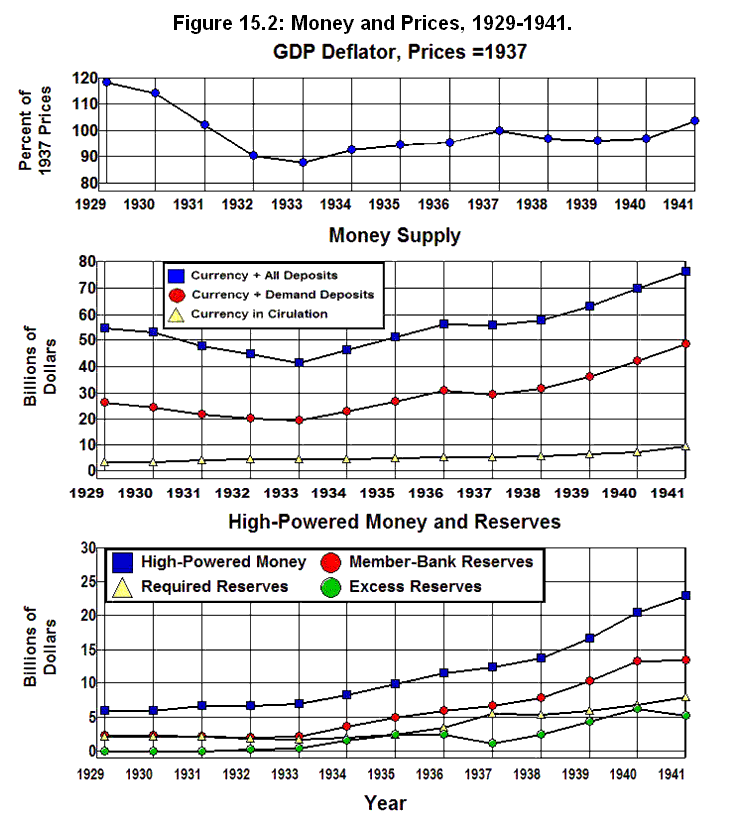

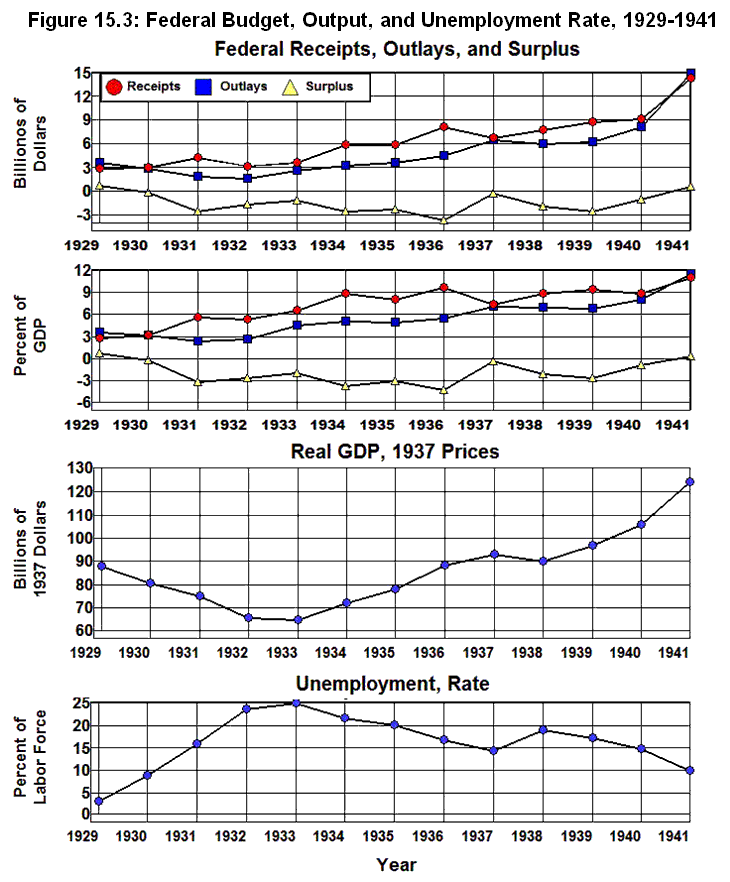

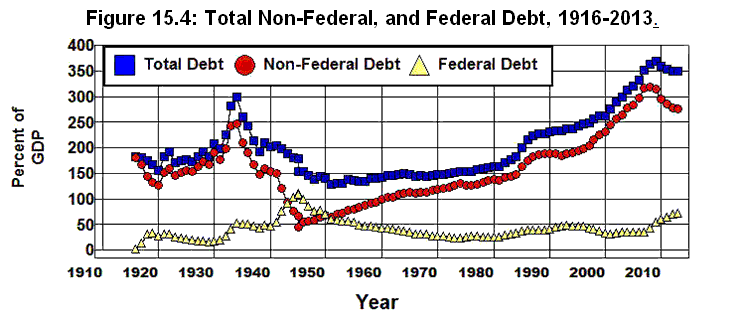

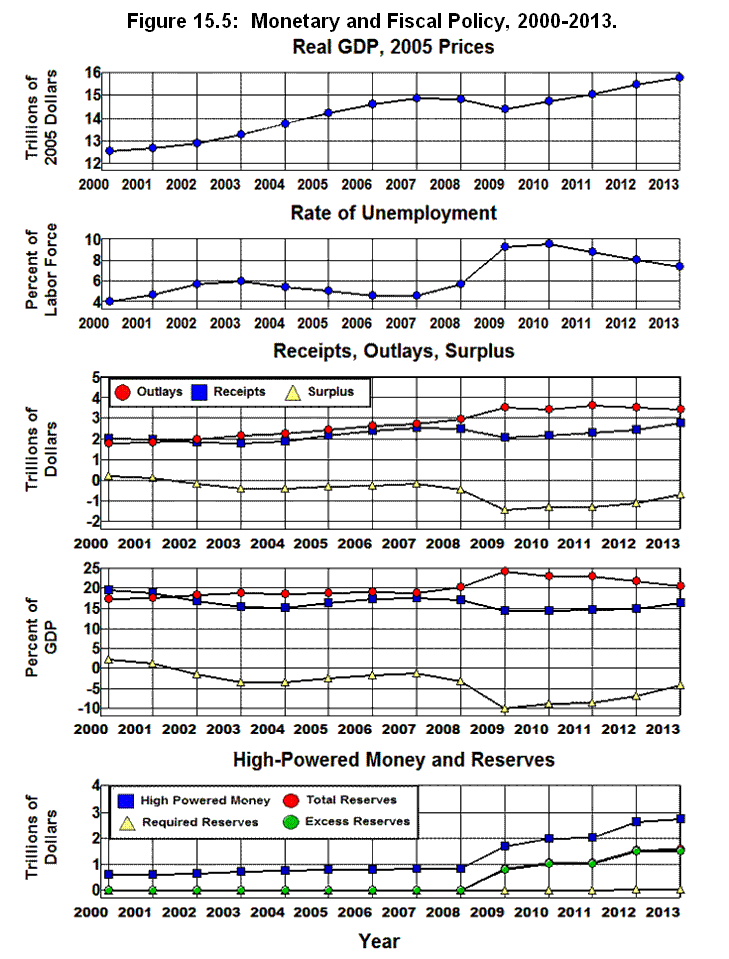

Chapter 15: Federal Versus Non-Federal Debt examines the fundamental difference between federal debt and non-federal debt and the lessons that should have been learned from the 1930s with regard to the importance of this difference as it relates to the stability of the economic system. It is argued that the most serious problem we face today is our non-federal debt, not our federal debt, and that it was the attempt to follow conservative fiscal and monetary policies from 1929 through 1933 that drove us into the debts of the Great Depression. It is also argued that the way in which our debt problem was solved during the 1930s and 1940s was by increasing economic growth, and the way the economic growth that solved our debt problem and took us out of the Great Depression was through a massive increase in government expenditures that was accompanied by dramatic increases in taxes.

Finally, is argued that none of the lessons that should have been learned from our experiences in the 1930s through the 1970s with regard to the federal debt have been learned by the free-market ideologues whose only vision for the future is lower taxes, less government, deregulation, and paying off the national debt. It is further argued that one of the lessons that should have been learned—namely, the need for higher taxes in this situation—has not been learned even by most of those who have learned the other lessons that should have been learned from our experiences of the 1930s through the 1970s.

Chapter 16: Managing the Federal Budget examines the fiscal problems we face. It is argued that if the government is to be made fiscally sound we must provide the government services that the people demand, and then collect the taxes necessary to pay for these services. It is further argued that this could be done quite easily by 1) rescinding the 2001-2003 Bush tax cuts, 2) eliminating unwarranted tax deductions and credits, 3) increasing the top marginal tax rates, and 4) increasing taxes on corporations.

It is also argued that if those who benefit the most from our economic system do not pay back in taxes enough to rebuild the public infrastructure and social capital that is consumed in the process of reaping the benefits they gained from our economic system, there is little hope for the future. It is further argued that this does not mean just the top one or two percent of the income distribution must pay back. It means that everyone who is capable of making a contribution toward this end must do their part. If this is not done we will consume the public resources that were left for us by previous generations, and in failing to replenish those resources, we will limit the economic possibilities for future generations.

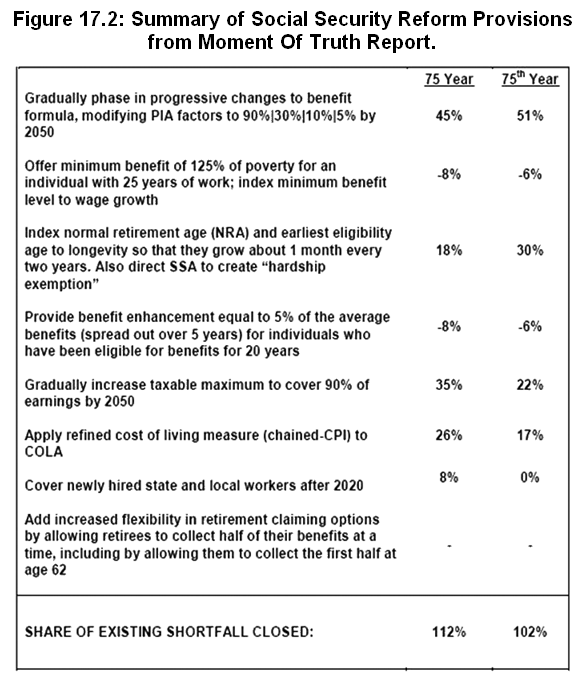

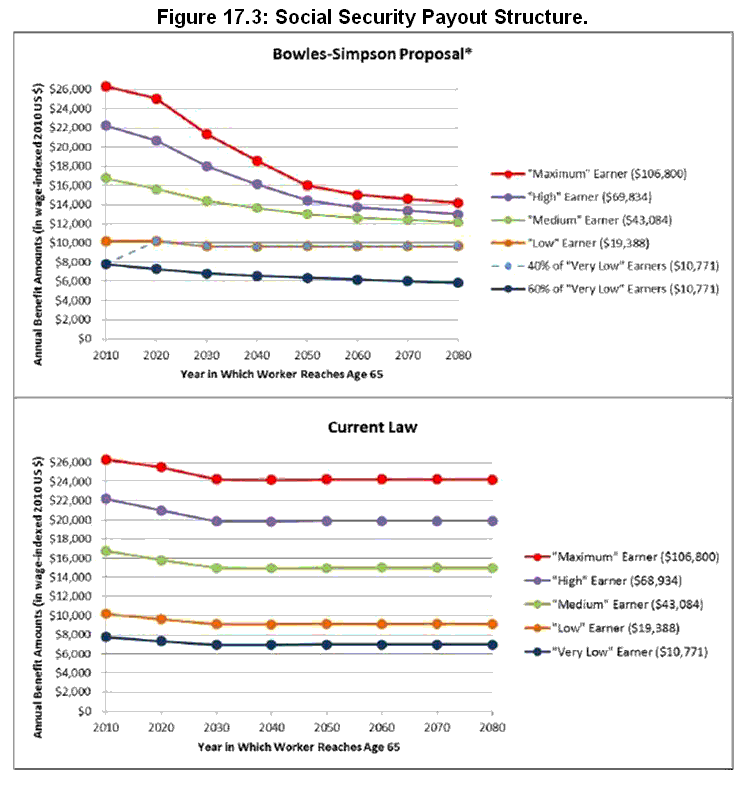

Chapter 17: Social Security, Healthcare, and Taxes looks at the problems created by the baby boomers retiring with regard to Social Security, Medicare, and the federal budget.

The Moment of Truth report written by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson is examined in detail in this chapter and is found wanting. It is argued that there are many ways to deal with the relatively minor problems posed by the baby boomers retiring when it comes to Social Security that do not involve the drastic changes in Social Security called for by Bowles and Simpson. At the same time, it is argued that containing the cost of Medicare is a serious problem and that the engine that drives up cost in the Medicare program is to be found in the private healthcare system, not in Medicare itself.It is argued that t

he most obvious, simplest, most efficient, and most cost effective way to deal with this problem would be to extend the Medicare program to the entire population, thereby, providing a mechanism by which costs in the entire system can be controlled. It is further argued that if we are to preserve Social Security and Medicare and, at the same time, provide all of the other government programs and services demanded by the American people in a fiscally responsible way, we must raise taxes.Chapter 18: Ideology Versus Reality examines the extent to which free-market ideologues fail to perceive the real world as it actually is and the consequences to society that result from their failure to come to grips with reality. It is argued that this ideological view is based on a straw-man caricature of government that completely ignores all of the essential functions that government performs in our daily lives and without which civilized society is impossible, and the academic model that explains how, and under what circumstances a free-market economy is supposed to work not only completely ignores the role of government in our economic and social lives, but the assumptions on which the logical consistency of this model depends are impossible to achieve in the real world.

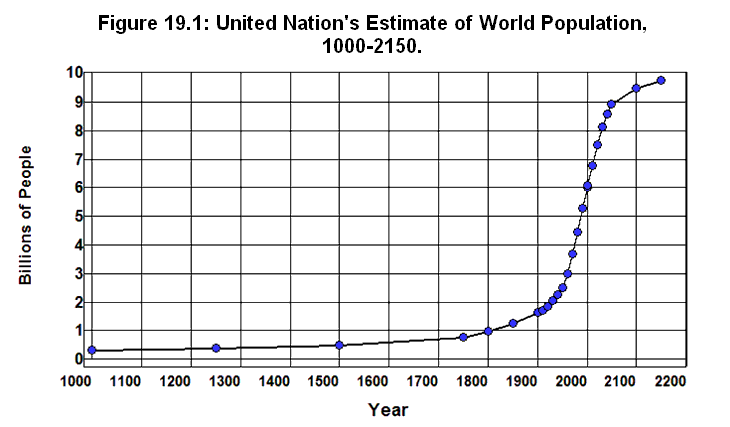

Chapter 19: Beyond the Current Crisis goes beyond the current economic disaster caused by deregulating the world’s financial system. It is argued that globalization, combined with technological improvements in transportation and communication over the past thirty years have led to incredible growth in productivity and output throughout the world. Unfortunately, this growth is derived from the same failed, nineteenth-century ideological paradigm of free-market capitalism that led to the deregulation of our financial system.

This paradigm is terribly flawed in its failure to understand the necessity to regulate pollution and to preserve our natural resources. If we value the kind of world we leave to our children and grandchildren we cannot sit back and hope for the best as unregulated markets squander our natural resources and pollute our planet. It is argued that the problems posed by population growth, the worldwide drive to industrialize, and the finite nature of our natural resources cannot be solved by markets alone. They can only be solved through the international cooperation of governments.

Autobiographical Information and Acknowledgements provides some autobiographical information and attempts to acknowledge the contributions others have made to whatever accomplishment I may have achieved in life.

Selective Bibliography lists a number of books that have contributed to my understanding of how the world works.

![]()

Chapter 1: Income, Fraud, Corruption, and Efficiency

George H. Blackford © 2009, last updated 5/1/2014

![]()

There’s class

warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class,

that’s making war, and we’re winning.

Warren E. Buffett

Changes in the economic landscape over the forty years leading up to the 2007 financial crisis are astounding. This is particularly true when it comes to changes in the tax code. The maximum marginal income tax was reduced from 70% to 35%, the maximum capital gains tax from 28% to 15.7%, the maximum corporate profits tax from 50% to 34%, the maximum tax on dividends from 70% to 15%, and the maximum marginal estate tax from 70% to 35%. At the same time, payroll taxes were increased as were taxes on cigarettes, alcohol, and other sales and excise taxes as government fees and fines and the tuition at public colleges and universities were increased as well. All of these changes have made our system of government finance more regressive—that is, they increased the proportion of income taken by the government from low and middle-income groups relative to the proportion taken from upper-income groups. (PCCW)

Changes in the area of market regulation have been particularly dramatic as well. Much of our regulatory system had been dismantled, either through legislative changes, deliberate under funding of the regulatory agencies, or through the appointment of individuals to head these agencies who did not believe in regulating markets and were willing to restrict the enforcement of existing regulations. (Frank Kuttner Amy NYT Bair)

A third area of economic policy in which there have been profound changes is in the area of international finance and trade. Of particular importance was the abandonment in 1973 of the managed international exchange system set up by the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944 and replacing it with what became known as the Washington Consensus which championed unrestricted international finance and trade. This eventually led to innumerable bilateral trade agreements negotiated with China since Nixon's historic visit in 1972, the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, and our joining the World Trade Organization in 1995. (Mavroudeas Stiglitz Galbraith Reinhart Philips Morris Eichengreen Rodrik)

All of these changes were championed in the name of economic efficiency and have, in fact, made it possible for countless individuals to amass huge amounts of wealth over the past forty years. What’s wrong with that? Haven’t we all benefited from the generation of all that wealth? Well, not exactly.

Changes in the Distribution of Income

It is instructive to look at how the distribution of income has changed since the onset of the changes in economic policy mentioned above.

Bottom 90%

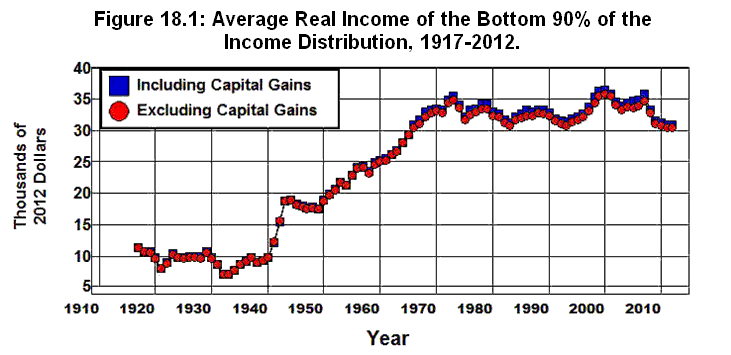

Figure 1.1 shows the average real income, both including and excluding capital gains, measured in 2012 prices, of all families in the bottom 90% of the income distribution in the United States from 1917 through 2012. In 2012 this group consisted of 145 million families that received an income (including capital gains) of $113,820 or less. The average income for this group was $30,997 in 2012.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

It is clear from Figure 1.1 that the 90% of the families at the bottom of the income distribution did not benefit at all from the increase in income that occurred from 1973 through 2012. While the average real income of this group rose dramatically from 1933 through 1973, increasing by a factor of 5, it trended downward from 1973 through the 1980s and didn't start to trend upward again until 1993. This upward trend was short lived, however, as the real income for the lower 90% began to decrease again after 2000.

The average real income of the bottom 90% of the income distribution actually fell by 13% during the 39 year period from 1973 through 2012. This 13% decrease provides a stark contrast to the 368% increase in real income this group experienced in the 39-year period that proceeded 1973. In absolute terms, average real income increased by $27,985 from 1934 through 1973 and fell by $4,587 from 1973 through 2012. The $30,997 average income the bottom 90% of the income distribution received in 2012 was actually less than the $31,006 average this income group received 46 years ago in 1966.

The fall in average real income from 1973 through 2012 received by the bottom 90% of the income distribution is particularly stark in light of the 104% increase in productivity that took place in the economy during this period. None of the benefits of this increase in productivity went to the bottom 90% of the income distribution. (Saez Gordon Sum)

Top 90-99%

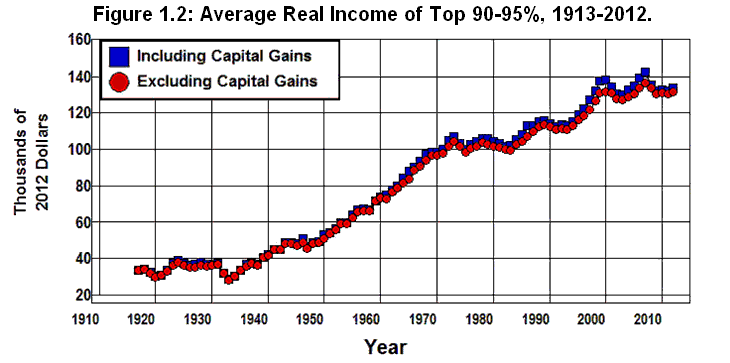

As is indicated in Figure 1.2, the situation was somewhat better for families in the top 90 to 95% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of the 8.0 million families that received an income between $113,820 and $161,438. The 2012 average income for this group was $133,530.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

Like the bottom 90%, the average real income of this group rose dramatically from 1933 through 1973, increasing by a factor of 3.75. After 1973, its average income leveled off but began an upward trend in 1982 that peaked in 2000 and again in 2007. It then receded somewhat by 2012. While the average real income of this top 90 to 95% of the population did increase by 25% from 1973 through 2012, this increase for that 39-year period was a mere fraction of the 251% increase this group experienced during the 39 years that proceeded 1973 and a third ($26,704) of the $76,375 increase this group received in absolute terms during this 39-year period.

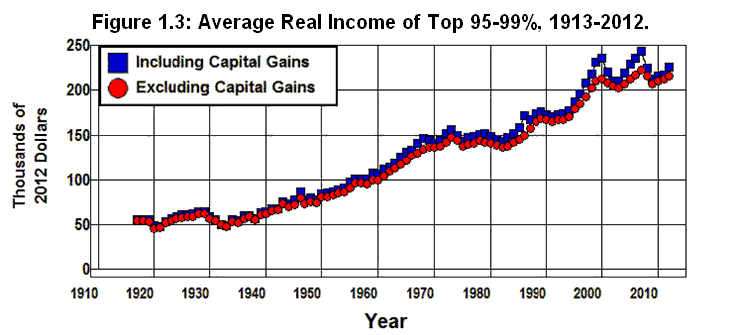

The pattern in Figure 1.2 repeats itself in Figure 1.3 for the next 4% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of 6.4 million families that received between $161,438 and $393,941, and the 2012 average income for this group was $226,405. The 44% increase in real income for this group for the 39-year period following 1973 was, again, far less than the 187% increase for this group during the 39-year period before 1973 and only 68% ($69,669) of the $102,127 increase they had received in absolute terms during this period.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

Top 1%

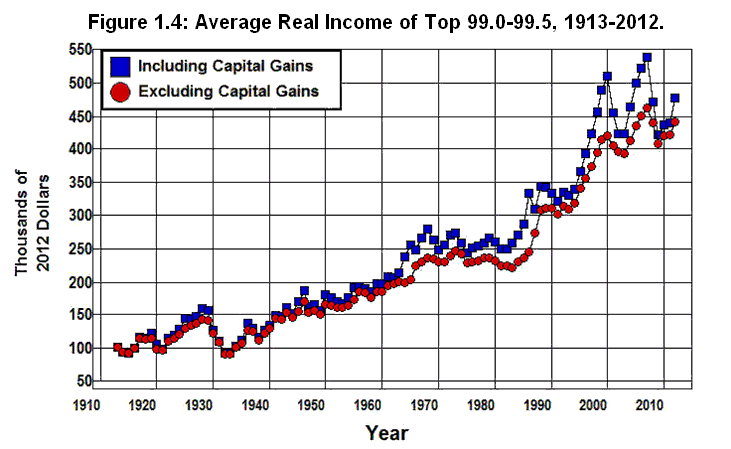

It's not until we get to the top 1% of the income distribution that this pattern changes, though not everyone in this group benefited equally. Figure 1.4 shows the average income of the top 99.0 to 99.5% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of 803,405 families that received between $393,941 and $611,805 with an average income of $477,738.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

The average real income of this group increased by 74% during the 39-year period from 1973 through 2012, a significant improvement over lower-income groups. Even though this is less than half of the 165% increase this group received in the 40-year period preceding 1973, the $203,097 increase in real income that took place from 1973 through 2012 is at least greater than the $171,155 increase in real income that this group received from 1934 through 1973.

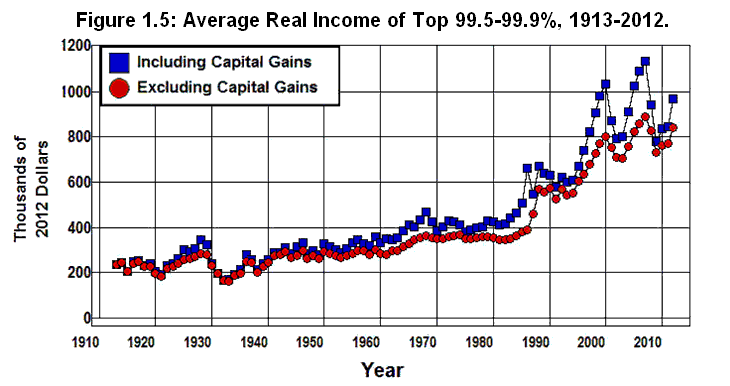

It's not until we get to the top 1/2 of the top 1%, however, that we come to the first income group that unambiguously benefited from the changes in tax, deregulatory, and international policies wrought by the policy changes that have taken place during the past forty years. Figure 1.5 through Figure 1.7 break down the top half of the top1% of the income distribution into three Groups:

Figure 1.5 shows the average income of the top 99.5 to 99.9% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of 642,724 families that received incomes between $611,805 and $1,906,047 with an average income of $969,544.

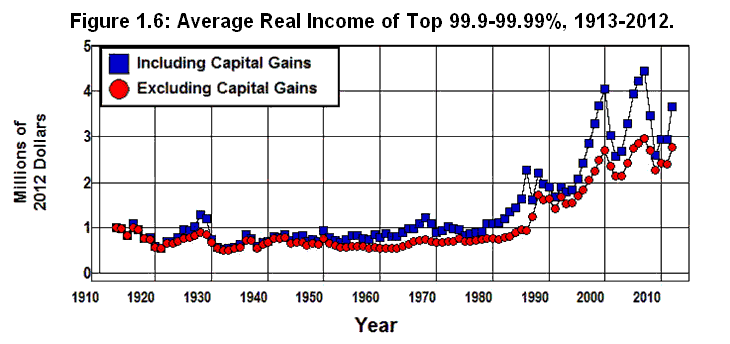

Figure 1.6 shows the average income of the top 99.9 to 99.99% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of 144,613 families that received incomes between $1,906,047 and $10,256,235 with an average income of $3,661,347.

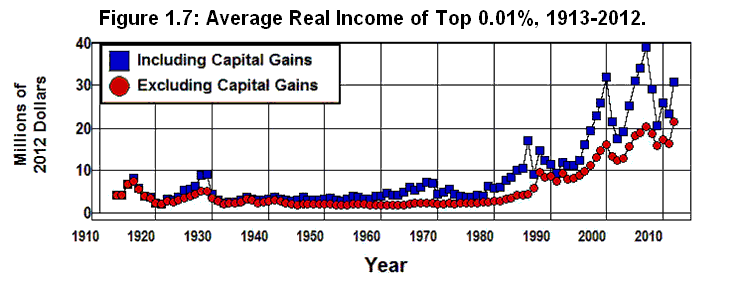

Figure 1.7 shows the average income of the top 0.01% of the income distribution. In 2012, this group consisted of 16,068 families with incomes equal to or above $10,256,235 with an average income of $30,785,699.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

Here are the true benefactors of the changes in tax, deregulation, and international trade policies over the past forty years. While the average real income of the bottom 90% of the population fell from $36 thousand a year in 1973 to $31 thousand a year in 2012, the average real income of the top 0.5% of the population more than tripled:

For the top 99.5-99.9% it went from $426 thousand to $970 thousand a year, a $544 thousand increase compared to a $231 thousand increase from 1934 through 1973.

For the top 99.9-99.99% it went from $971 thousand to $3.7 million a year, a $2.7 million increase compared to a $402 thousand increase from 1934 through 1973.

And for the top .01% it went from $4.5 million to $30.8 million a year, a $26.3 million increase compared to a $1.9 million increase from 1934 through 1973, all measured in 2012 dollars.

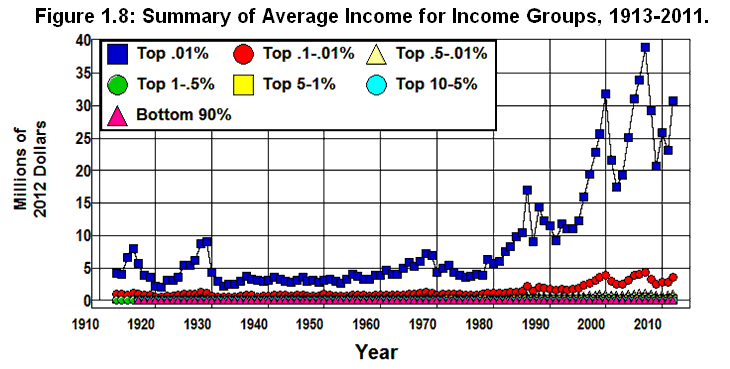

The relative magnitudes of the numbers involved can be seen in Figure 1.8 which plots the average incomes (including capital gains) of the various income groups from 1913 through 2011 on the same scale.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

Summary

This is what the changes in economic policy in the name of free-market capitalism and economic efficiency over the past forty years have led to, namely, a huge windfall for the upper 0.5% of the income distribution, a net loss for the bottom 90% of the income distribution, and relatively little if anything for the 90-99.5% of the income distribution in between. (Piketty Saez Gordon Sum) What's more, the situation is even worse for those families at the bottom 90% of the income distribution than the above numbers indicate.

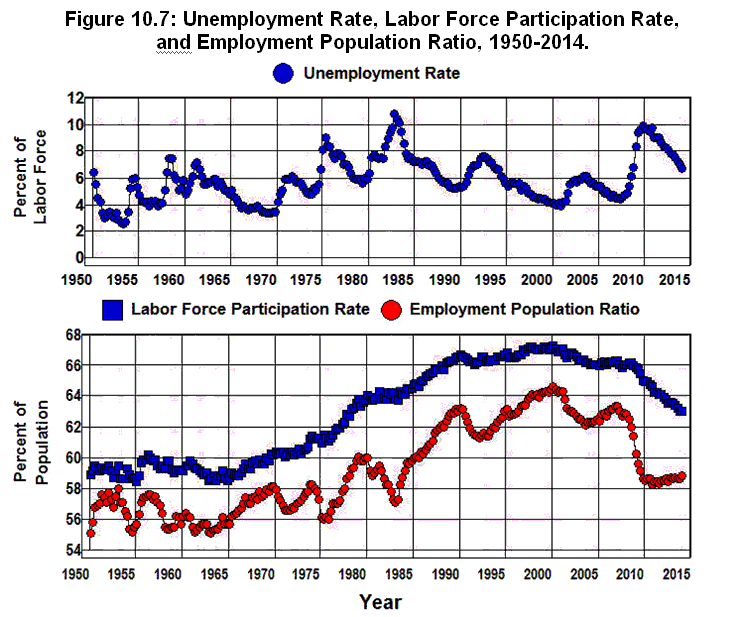

The average income of the bottom 90% would have fallen even further than the 13% indicated in Figure 1.1 were it not for the fact that the percentage of women who participate in the labor force has increased over 30% since 1973. This suggests that the number of two income families in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution must have increased significantly during this period as mothers were forced to leave their children to the care of others and enter the labor force in order to maintain their family's standard of living.

When this is combined with a more highly regressive tax structure—higher payroll taxes, excise taxes, fines and fees, and higher tuition at public colleges and universities—it is clear that the 90% of the population at the bottom of the income distribution is significantly worse off today than it was forty years ago.

Deregulation and the Savings and Loans

The effects of changes in regulatory policy began to manifest themselves early in the1980s after the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 and Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act were passed. These acts 1) lessened the capital and reserve requirements of banks, 2) provided mechanisms to assist failing banks rather than closing them down, 3) phased out interest rate ceilings on bank deposits, and 4) expanded the kinds of loans thrifts (savings and loans and savings banks) could make so as to allow them to become more like commercial banks. (FDIC) The purpose of these acts was to enhance the level of competition in the financial markets in order to improve the economic efficiency in these markets. This is not exactly how this grand experiment in deregulation worked out.

The early 1980s was a particularly ominous time to deregulate the savings and loans. At the end of the 1981 recession 10% of the savings and loans were insolvent on an accounting basis, and institutions that had no tangible equity at all controlled 35% of the industry's assets. (Black FDIC) These savings and loans—with their federally insured deposits—were allowed to compete on an equal footing with the rest of the financial system in spite of the fact that insolvent financial institutions have nothing to lose by rolling the dice and betting the farm on high stakes investments in trying to recoup their losses. After all, if they win they keep it all. If they lose, they just increase their insolvency, and since they were bankrupt to start with, they are no worse off than they were before. Their investors and taxpayers take the increased losses if they lose, not the owners and managers of the savings and loans. (Garcia)

What's more, the reduced regulation and supervision created innumerable opportunities to exploit the system through fraud. As a result, the character of the savings and loan industry changed after deregulation as a new breed of owners, such as Charles H. Keating and Hal Greenwood Jr., began to shift out of home mortgages and into commercial real estate loans, direct investments in real estate projects, junk bonds and other securities, and innumerable other risky areas where the potential for fraud abounds—areas they had been barred from entering since the 1930s as a result of the lessons learned from the 1920s. (FDIC Black Akerlof Stewart)

There was a virtual explosion in Acquisition, Development, and Construction (ADC) loans issued by savings and loans following deregulation whereby real estate developers were allowed to borrow money for a project with no interest or principal payments for three years. The savings and loans added huge fees to these loans, which they booked as income in the year the loans were made. The interest was also booked as income as it accrued over the three years of the loan even though no interest was paid. This led, through the magic of accounting, to huge paper profits out of which the owners and managers of the savings and loans paid themselves huge dividends, salaries, and bonuses in real cash even though no cash had been received for fees or interest owed.

What happened when the loans came due and the developers couldn't pay? No problem. The savings and loans just refinanced the loans, added more fees and interest to the principal, booked more paper fee and interest income, and paid themselves more dividends, salaries, and bonuses in real cash. And they were allowed to finance all of this through brokered deposits—federally insured certificates of deposit that were sold by brokerage firms, such as Merrill Lynch, to investors all over the country. The money from federally insured brokered deposits allowed the savings and loans to expand their deposit base, expand their ADC loans, finance innumerable other fraudulent schemes, increase their paper profits, and to come up with the real cash necessary to finance the huge payments of dividends, salaries, and bonuses that their managers and owners took out of these institutions. (Black Akerlof Stewart FDIC)

While this was going on, the inflow of credit into a number of regional commercial real estate markets that accompanied this expansion of savings and loan activity, mostly in the Southwest and Northeast, started speculative booms in these markets. As these bubbles developed, the fraudulently managed institutions began to threaten the honestly managed institutions—not just among the savings and loans but among the savings and commercial banks as well. Fraudulently managed savings and loans bid fiercely for brokered deposits as they bid up the rates paid on these deposits. This, in turn, increased costs in the entire financial system as the fraudulently managed savings and loans dug the hole deeper for everyone. Honestly managed institutions that were forced to, or were naively willing to invest in the booming commercial real estate markets made the situation worse.

ADC scams were not the only scams that followed in the wake of the deregulation of the early 1980s. Deregulation made it possible for Michael Milken and other corporate raiders of the 1980s to finance their leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers by funneling the junk bonds they issued into captive savings and loans as they used the assets of the target companies as collateral for the junk bonds they issued. The proceeds from the sale of those bonds were then used not only to payoff the existing stockholders but to pay huge dividends and bonuses to the raiders themselves as the companies taken over were driven into bankruptcy along with the savings and loans that financed them.

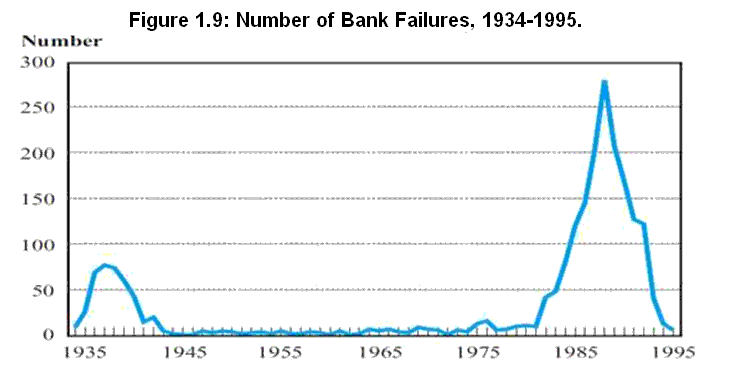

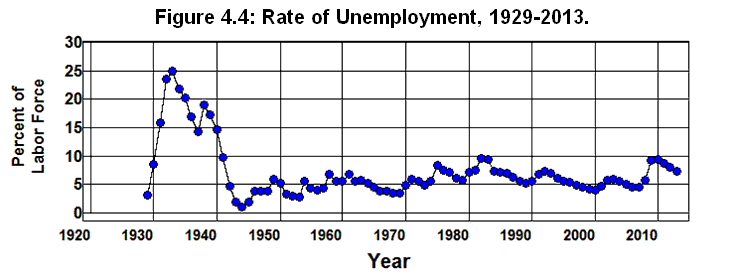

As the speculative bubbles in the markets fueled by ADC scams burst and the companies taken over in junk bond scams began to go bankrupt toward the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s, the result was the first major financial crisis in the United States since the Great Depression. (FDIC) In the end, some 1,300 savings institutions failed, along with 1,600 banks. That amounted to almost a third of all savings institutions along with 10% of all banks in existence at the time. By comparison, only 243 banks failed between 1934 and 1980. In addition, some 300 fraudulently run savings and loans that were nothing more than Ponzi schemes failed at the peak of this disaster.

In the end, the corporate raiders and owners and managers of the savings and loans walked away with billions, and the tax payers took the losses. It costs the American taxpayer $130 billion to reimburse the depositors in these failed institutions. In addition, the resulting financial crisis was a precursor to the 1990-1991 recession. (Black FDIC Krugman Akerlof Stewart)

While the number of banks that failed during this crisis was only a third of the number that failed during the Great Depression, the extraordinary nature of the savings and loan crisis is indicated by the graph constructed by the FDIC that is displayed in Figure 1.9. This chart shows the number of FDIC insured commercial and savings banks that failed each year from 1934 through 1995. While it includes only the 1,600 FDIC insured institutions that failed and does not include the 1,300 failed savings and loans insured by the FSLIC, it clearly indicates the degree of stability in the system since the end of World War II through the 1970s before the era of deregulation began in earnest, and the degree to which deregulation in the 1980s destabilized the system.

Source: FDIC

The Rise of Predatory Finance and Corruption

While there was an attempt by Congress to reregulate the financial markets in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and taxes were raised somewhat during the late Bush I and early Clinton administrations, (TF TAP) the cat was out of the bag. The fortunes made by those who looted the savings and loans during the 1980s clearly demonstrated how lower tax rates on unearned and ultra high incomes combined with a lack of oversight on the part of government regulators made it possible for fortunes to be made by those willing to bend or ignore the law. Even though over a thousand individuals associated with the savings and loan debacle were convicted of felonies, most walked away with their fortunes intact. (Black Akerlof Stewart) This was the lesson learned by those at the top of the economic food chain, and this same lesson was drawn from the experiences in other industries as well.

Throughout the 1980s, fortunes were made through junk bond financing of hostile takeovers and leveraged buyouts that led to the dissolution of American companies, repression of wages, the looting of corporate pension funds and other assets, and the outsourcing of American jobs overseas and to Mexico. (Stewart Smith) Usury laws were repealed throughout the country, and credit card companies were allowed to charge exorbitant interest rates, exact unreasonable fees, and to manipulate payment dates and the dates at which payments were recorded to force customers to pay late charges even though they had mailed their payments on time. (PRIG) At the same time, credit card companies devised elaborate schemes to lure naive and financially unsophisticated customers deeper and deeper into debt. (Frontline MSN)

With so much money involved, the lack of government regulation allowed the entire fiduciary structure of our economic and political systems to become corrupted. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s stockholders lost control of corporations as the corporate governance structure broke down. Boards of directors became vassals of their CEOs, and management salaries and bonuses soared to astronomical levels. The major accounting firms found they could make more money advising corporations how to make paper profits in order to justify increases in management salaries and bonuses than they could by providing independent audits of companies' books for stockholders. Brokerage firms found they could make more money hyping worthless mutual funds and internet, energy, and telecom stocks than they could by providing sound investment advice to their clients. Investment banks found it more profitable to dissolve their partnerships, become corporations, and speculate for their own account with investors' money than to provide underwriting and advisory services to their clients. (Bogle Galbraith Stewart Baker Kuttner Phillips)

All of this involved huge conflicts of interest between corporation and mutual fund managers and the stockholders these managers are supposed to serve, accounting firms and the investing public the accounting firms are supposed to serve, brokerage firms and the investors the brokerage firms are supposed to serve, and investment banks and the businesses the investment bankers are supposed to serve. These conflicts of interest contributed directly to the Drexel Burnham Lambert, Charles Keating, Michael Milken, Ivan Boesky, and other insider trading, junk bond, and Savings and Loan frauds that were a direct cause of the junk bond, and commercial real estate bubbles of the 1980s, the bursting of which was a precursor to the 1990-1991 recession. They also contributed directly to the HomeStore/AOL, Enron, Global Crossing, and WorldCom frauds that were a direct cause of the dotcom and telecom bubbles of the 1990s, the bursting of which led to the 2001 recession.

In addition, throughout this entire period, antitrust laws were ignored as corporations were allowed to merge into mega institutions with overwhelming economic and political power. Laws against interstate banking were repealed in 1994, (IBBEA) and as the banking industry began to concentrate its power, key regulatory constraints on the financial system were removed in 1999 with the repeal of the Glass-Steagall prohibition against commercial bank holding companies becoming conglomerates that provide both commercial and investment banking services along with insurance and brokerage services. (FSMA) In 2000, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act which blocked attempts to regulate the derivatives markets was passed.

These changes made possible the accumulation of wealth in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s at levels that were heretofore unimaginable. Along with that wealth came unimaginable levels of economic and political power. And along with that power came a virtual collapse of integrity in our financial and political systems. In the wake of the dotcom and telecom bubbles bursting and the collapse of the HomeStore/AOL, Enron, Global Crossing, and WorldCom frauds, the mega banks and accounting firms that facilitated these frauds found they could make hundreds of billions of dollars by securitizing subprime mortgages. This discovery set in motion a set of forces that drove our economic system—along with that of the entire world—headlong into a catastrophe of epic proportions.

Securitization and the Crash of 2008

Securitizing subprime mortgages became so profitable that by the early 2000s there were not enough qualified subprime borrowers to meet the demands of the securitizers.[1.1] Rather than cut back their operations, predatory mortgage originators (such as Washington Mutual, Countrywide, IndyMac, New Century, Fremont Investment & Loan, and CitiFinancial) talked millions of naive people into applying for subprime mortgages by misrepresenting the nature of these mortgages. The most serious misrepresentation was to offer borrowers an adjustable rate, negative amortization mortgage with an unreasonably low teaser rate without explaining the effect on their monthly payment when the initial rate adjusted to the market rate. Using this and other ploys, borrowers who qualified for modest subprime mortgages at reasonable subprime rates, were talked into applying for exorbitant subprime mortgages at rates they could not afford. Even borrowers who qualified for modest prime rate mortgages at reasonable prime rates, were talked into applying for exorbitant subprime mortgages they could not afford. At the same time, borrowers not qualified for any kind of mortgage at all were approved for subprime mortgages. (Senate FCIC WSFC Spitzer)

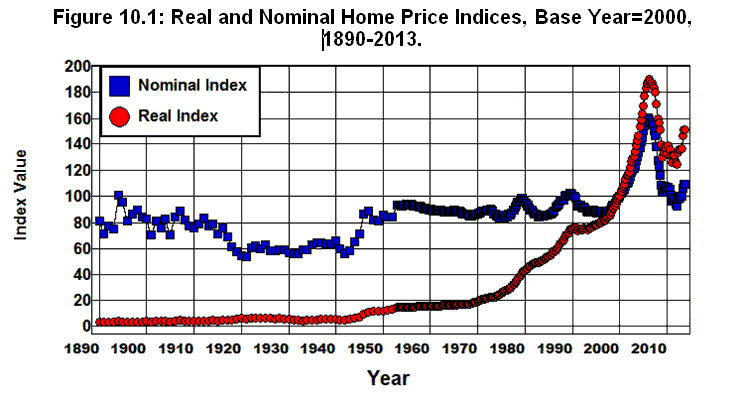

Next, in order to sell these mortgages it was necessary for mortgage originators to obtain appraisals of the underlying properties consistent with the values of the mortgages being originated. To obtain these appraisals mortgage originators shopped around for appraisers who would write consistent appraisals and shunned appraisers who would not. This guaranteed rising incomes for appraisers that cooperated with the mortgage originators and falling incomes for those that did not. At the same time, some lenders setup in-house mortgage appraisal subsidiaries so as to guarantee the kinds of appraisals they wanted. The result was a systematic upward bias in real-estate appraisals, and the flow of funds into the real estate sector led to a systematic upward bias in housing prices. (FCIC WSFC)

As it became more difficult to find subprime borrowers, the securitizers turned to alt-A borrowers. At this point real-estate speculators got into the act. As housing prices rose, speculators discovered they could get alt-A mortgages with little or no money down and without any verification of the assets, income, or employment status they reported on the applications for these loans. These no-doc loans, as they were called in the beginning, were soon to become known as ninja loans—short for No Income, No Job, and no Asset loans—or just plain liar loans. As a result, a host of speculators took out alt-A mortgages knowing that if the prices of their properties increased they would profit greatly, and if the prices of their properties went down they could walk away from these mortgages with little or no loss to themselves. When such financing was combined with fraudulently obtained appraisals, many speculators were able to walk away from their loans with a profit without making a single payment on their mortgage. (T2P Senate FCIC WSFC)

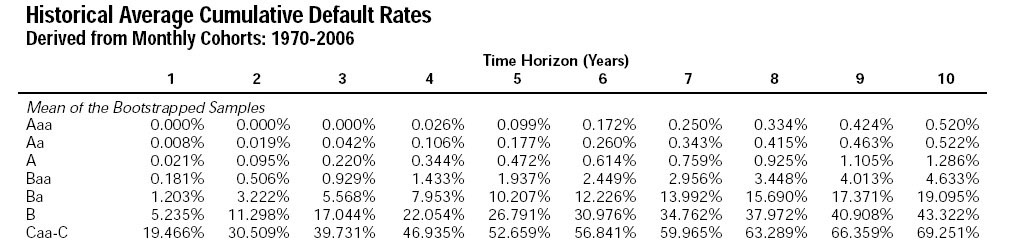

Firms that securitize mortgages were the next link in the financial food chain that fed off the subprime and alt-A mortgages. In order for investment banks and other firms that securitized mortgages to sell the Mortgage Backed Securities (MBSs) at the highest possible price they had to receive the highest possible ratings from a bond rating agency. To accomplish this, the securitizers followed the lead of the mortgage originators to steer their business to bond rating agencies that gave them the highest ratings and away from those that gave them lower ratings. In this way the companies that securitized mortgages were able to get the three major bond rating agencies (Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, and Fitch) to give triple-A ratings to mortgage backed securities even though the rating agencies had no creditable basis on which to rate these securities. (House FCIC WSFC)

From 2002 through 2007, literally millions of fraudulent obtained subprime and alt-A mortgages provided the collateral for trillions of dollars of Mortgage Backed Securities (MBSs) that were spread throughout the financial system of the entire world. (T2P FCIC WSFC) As these toxic MBSs spread around the world—as well as into banks, insurance companies, pension funds, money market funds, mutual funds, and institutional endowment funds at home—hundreds of billions of dollars were paid out in salaries, bonuses, and dividends to those who participated in the securitization process. Even the managers of the banks, insurance companies, and mutual and endowment funds that bought these toxic assets—and whose stock holders eventually suffered losses as a result—were paid billions of dollars as their paper profits grew along with the housing bubble.

Huge fortunes were amassed as this process grew beyond all bounds of reason, and as the fraud grew in the subprime and alt-A mortgage markets the officials in control of the federal government during the Bush II administration did nothing to stop it. When state or local authorities complained to the federal government about the predatory lending practices in their communities, not only did the Federal Reserve—which had the absolute authority under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) to stop these practices (Natter WSFC)—do nothing to clamp down on the predatory practices in the mortgage market, the Bush II Justice Department actually went to court to keep state and local authorities from regulating this market. (Spitzer FCIC WSFC) As a result, no restraints were placed on the mortgage originators, securitizers, or bond rating agencies as the entire securitization process became corrupted.

The resulting housing bubble grew dramatically in the early 2000s, and as with all speculative bubbles, it was only a matter of time before it burst. By the time it did, $10 trillion worth of mortgages on residential properties with inflated prices were created that could not sustain their value. To make things worse, virtually all of the worst of the worst mortgages—the fraudulently obtained subprime and alt-A mortgages—were bundled into Mortgage Backed Securities and sold all over the world, and over half of the triple-A rated tranches of those MBSs ended up on the books of our own financial institutions—on the books of investment and commercial banks, money market funds, mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies throughout the country. (NYU)

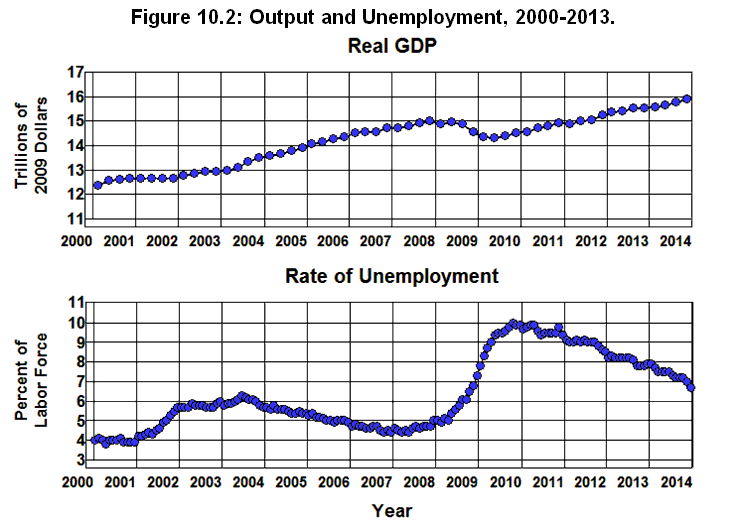

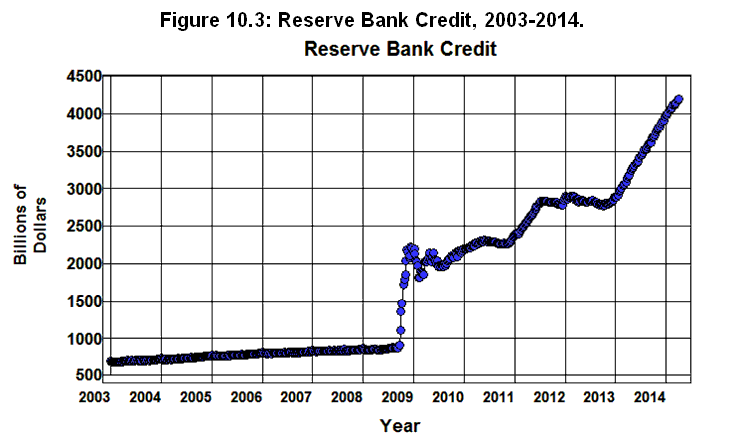

As housing prices began to fall, the Mortgage Backed Securities that were created while housing prices were driven up to unsustainable levels lost their value and the ensuing panic drove all of the investment banks and most of the major commercial banks in our country into insolvency. To keep the financial system from collapsing and driving the economy into a depression comparable to that of the 1930s, the government had to step in and prop up the financial system with $700 billion in TARP funds. At the same time, the Federal Reserve was forced to increase reserve bank credit by over $1.5 trillion dollars in order to end the resulting run on the financial system. In the meantime, the unemployment rate hit 10%; trillions of dollars of wealth held by insurance companies, mutual funds, pension funds, and 401Ks evaporated, and the financial and international exchange systems of the entire world were destabilized as a worldwide economic crisis followed in the wake of this disaster. (Stiglitz NYU FCIC WSFC)

Speculative Bubbles and Economic Efficiency

The securitization of fraudulently obtained subprime and alt-A mortgages in the early to mid 2000s was, undoubtedly, the greatest fraud in history, one that sent shockwaves throughout the entire world. Those who bought homes during the housing bubble facilitated by this fraud, whose pension plans were invested in the toxic assets created as a result of this bubble, who had a stake in the endowment and mutual funds that invested in these assets, the small investors with 401Ks, those who depend on wages and salaries for their livelihood and found themselves unemployed as a result of the economic collapse caused by the bursting of the housing bubble, and those who lost their homes as a result of the collapsing housing market and the recession that followed were particularly hard hit by the economic catastrophe that followed in the wake of this disaster. At the same time, many, if not most of those who stood at the center of this fraud made fortunes. (FCIC WSFC)

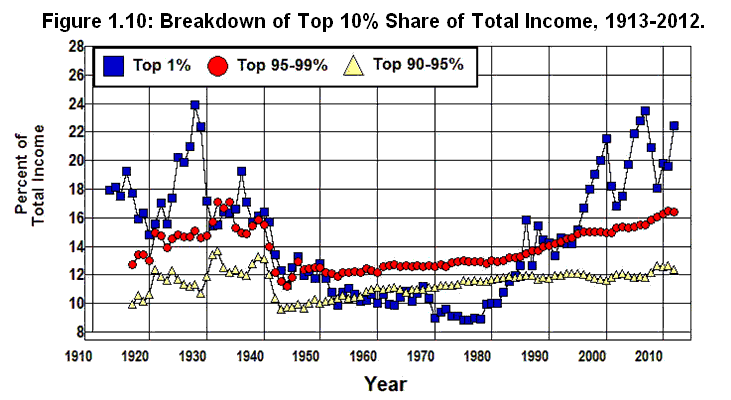

The same is true of the economic disasters that followed the hostile takeover/leverage buyout craze and the savings and loan fiasco of the 1980s and the dotcom and telecom bubbles of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Huge profits, bonuses, and windfall gains were generated as asset prices were bid up in the process of creating these speculative bubbles, and all of these bubbles were precursors to economic catastrophes. (Stewart FCIC WSFC) The extent to which this is so is shown in Figure 1.10through Figure 1.12.

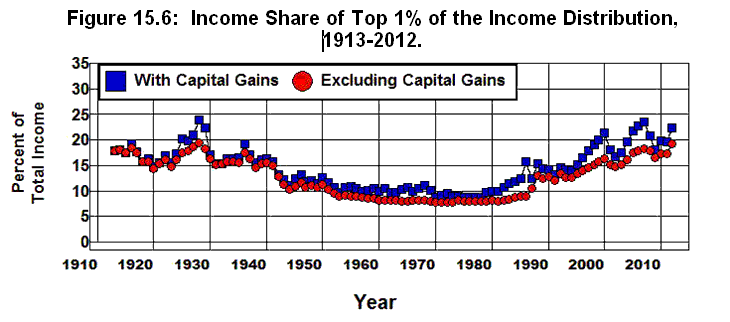

Figure 1.10 provides a breakdown of the share of total income (including capital gains) that went to the top 10% of the income distribution from 1913 through 2010. This graph shows the relative stability of the share of total income of the top 90-99% of the income distribution since1945 compared to that of the top 1%. It also shows the volatility of the share of total income that went to the top 1% before 1945 and after 1980 compared to the relative stability of the share this group received in the period of restrictive financial regulation from 1945 to 1980. Of particular interest is the way in which the volatility of the top 1% is tied to speculative bubbles.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

The extent to which the top 1% of the income distribution benefited from these bubbles is clearly shown in Figure 1.10 by:

the 53% increase in income share this group received during the 1921-1926 real estate bubble and the 1926-1929 stock market bubble that led up to the Great Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s,

the 55% increase in income share this group received during the 1981-1988 junk bond, and commercial real estate bubbles of the 1980s that led up to savings and loan crisis and the 1990-1991 recession,

the 51% increase in income share this group received during the 1994-2000 dotcom and telecom bubbles that led up to the stock market crash of 2000 and the 2001 recession, and

the 39% increase in income share this group received during the 2002-2007 housing bubble that led up to the Great Crash of 2008 and the worldwide economic crisis we are in the midst of today.

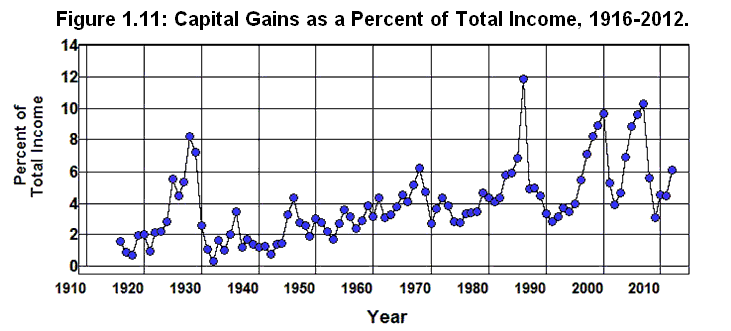

Similarly, Figure 1.11 shows the amount of income received in the form of capital gains as a percent of total income from 1916 through 2012. This figure displays a pattern similar to that in Figure 1.10 with relatively little volatility in the percent of total income received in the form of capital gains during the period of restrictive financial regulation from 1945 to 1980 compared to the preceding and following periods. While the 1986 spike in this graph conflates the effects of the anticipated 1987 increase in the capital gains tax with the effects of the stock market and commercial real estate bubbles of the 1980s, there were no capital gains tax increases in the 1920s, 1990s, or 2000s.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database.

The increase in capital gains by fully 6% of total income in the 1920s, 1990s, and 2000s depicted in Figure 1.11 clearly shows the effects of speculation on income during these eras that led to economic catastrophes as those who profited from these bubbles realized huge capital gains, and it is, perhaps, worth emphasizing here that these are realized capital gains. When the crash came there was someone or some institution on the other side of the sale that generated these realized capital gains that realized the loss including pension funds, insurance companies, 401ks, endowment funds, and taxpayers when depositors and financial institutions were bailed out.

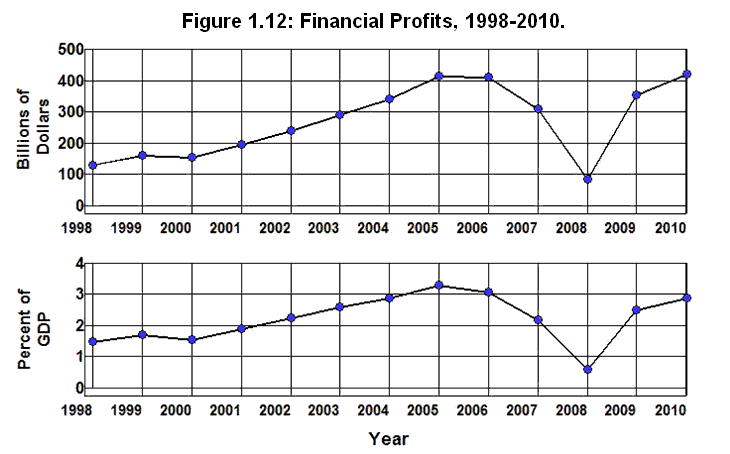

While Figure 1.10 and Figure 1.11 deal with family income, Figure 1.12 shows how the financial system fared through the housing bubble of the 2000s both in nominal terms and as a percent of GDP.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2012 (B91PDF|XLS);

Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.2.5).Of particular interest in Figure 1.12 is the 163% increase in financial sector profits from 2000 through 2006 following passage of the Financial Services Modernization Act in 1999 and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act in 2000. These two acts, combined with the refusal by the Bush II administration and the Greenspan Federal Reserve to enforce what little financial regulation remained gave the non-depository financial institutions a free hand to do just about whatever they wanted to do in the world of finance. What they wanted to do was securitize millions of fraudulently obtained subprime and alt-A mortgages and sell those mortgages all over the world. In the process they accumulated over a trillion dollars in additional profits from 2001 through 2007 in excess of what they would have made if there had been no housing bubble and their profits had stayed at their 2000 level.

Deregulation of the financial markets was done in the name of economic efficiency, but the massive fortunes made in the process of creating the dotcom and housing bubbles had nothing to do with economic efficiency. Nor were there economic efficiencies gained in the fortunes made in the commercial real estate and junk bond bubbles created during the savings and loan fiasco or in the leverage buyout/hostile takeover craze of the 1980s or in the credit card predation that has grown in such immense proportions during the past thirty years.

These fortunes were amassed in the process of squandering our economic resources on a massive scale as companies were driven dangerously into debt through leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers or in attempting to avoid such takeovers; funds were directed into sham internet companies, and resources were directed into the production of redundant telecom facilities and innumerable real estate projects that sat empty as the bubbles burst and millions of people lost their jobs, their homes, their pensions, their life savings, and their hopes and dreams for the future in the wake of the economic catastrophes that followed.

Economic efficiency means producing more with a given amount of resources toward the end of improving human well being. It’s not about transferring income and wealth from the bottom of the income distribution to the top. This transfer of income and wealth may seem efficient from the perspective of those at the top. It is clearly not efficient from the perspective of the vast majority of the population at the bottom. The suggestion that the policy changes that have occurred over the past forty years—policy changes that led to a collapse of the fiduciary structure of society, gave rise to massive frauds, generated massive rewards for those who perpetrated these frauds, and harmed the vast majority of the population to the benefit of the few—have somehow improved the economic efficiency of the American economy is absurd.

Over 8 million people had lost their jobs by 2010 as a result of the housing bubble bursting in 2006, and 4 million families lost their homes. In 2010, another 4.5 million families were seriously behind in their mortgage payment or in the process of foreclosure. “In the fall of 2010, 1 in every 11 outstanding residential mortgage loans in the United States was at least one payment past due but not yet in foreclosure.” Nationwide, 10.8 million families—22.5% of all families with mortgages—owed more on their mortgages in 2010 than their houses were worth. In Florida, Michigan, and Nevada more than 50% of all mortgages were underwater, and it is projected that by the time this crisis is over as many as 13 million families could lose their homes. (FCIC)

These numbers are the end result of the economic policy changes we have made over the past forty years, and there’s nothing efficient about them.

Endnote

[1.1] The basic mechanism by which securitization is accomplished, while complicated in practice, is fairly simple in principle:

First, the originator or sponsor of the securitization process forms a special corporation—generally referred to as a Special Purpose Vehicle or SPV—for the purpose of purchasing the assets to be securitized.

Second, the sponsor sells the assets to be securitized to the SPV.

Third, the SPV holds these assets in trust pledging the revenue from the assets as collateral for the securities issued by the SPV. The securities (bonds) issued by the SPV are referred to as Asset Backed Securities or ABSs since they are collateralized (backed) by the assets held in trust by the SPV. When the assets that back the SPV’s securities are mortgages, these securities are referred to as Mortgage Backed Securities or MBSs.

Finally, the proceeds from the sale of the ABSs issued by the SPV are used to pay the sponsor for the assets it sold to the SPV.

The sponsor makes money off this process by being able to sell its assets at a higher price to the SPV than it would otherwise be able to obtain and by charging the SPV an initial fee for setting up the securitization process. The sponsor may also receive a continuing management fee for managing the assets and liabilities of the SPV.

The above explanation has provided only the basics for understanding what securitization is about, and we will return to this subject in Chapter 8. For a more detailed explanation that is quite readable see the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission’s Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States.

![]()

Chapter 2: International Finance and Trade

George H. Blackford © 2009, last updated 5/1/2014

![]()

The American dollar became overvalued in the markets for international exchange in the late 1950s as Europe recovered from the devastation of World War II.[2.1] This problem came to a head in 1973 when the Nixon administration allowed the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement to collapse along with its fixed exchange rate system and its provisions for controlling international capital flows. International exchange rates have floated in unregulated markets ever since. As a result, the international exchange system has become the largest gambling casino in the history of man. Financial institutions place trillions of dollars of bets in this casino on a daily basis as they direct international capital flows throughout the world. Insiders who gamble in this market can make fortunes, but when things go wrong, the results can be catastrophic. (Mavroudeas EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

International Crises and Financial Bailouts

There have been four occasions since 1974 where the United States government has had to step in to bail out American financial institutions that bet wrong in this casino: The first was in the early 1980s during the Latin American Debt Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Latin American countries. The second was in 1994 during the Mexican Peso Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Mexico. The third was in 1998 when an American hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management, over extended itself throughout the entire world during the Asian Currency Crisis that precipitated the 1998 Russian Default. The fourth was in 2008 when the world financial system ground to a halt in the wake of the Subprime Mortgage Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves all over the world in marketing securities backed by fraudulently obtained mortgages.

All of these crises led to economic catastrophes—for the Latin American countries in the 1980s, for Mexico following the Peso Crisis in 1994, for Russia and the South and East Asian countries following the 1998 Asian Currency Crisis, and for most of the world following the worldwide financial crisis of 2008. At the same time, these crises were preceded by huge paper profits for the institutions that fostered the speculative bubbles that led to these crises as well as huge salaries and bonuses for the managers of these institutions. Those who were able to take advantage of these catastrophes made fortunes while most everyone else was left holding the bag. This is especially so for those who rely on wages and salaries for their livelihood, who are forced to live with the uncertainty and economic losses caused by these catastrophes, and whose taxes must pay for the economic bailouts that resulted. (Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

In addition to creating a cycle of international crises and bailouts, the officials in charge of our government have allowed the American dollar to be overvalued in international markets for much of the past thirty years. This act of misfeasance, malfeasance, or just plain incompetence has been so devastating to our economic system that it will take decades, if not generations, to repair the damage. (Phillips Eichengreen)

The Overvalued Dollar and Trade

In theory, the interaction of supply and demand in the markets for international exchange is supposed to yield an optimal allocation of international investment, production, and consumption. But this theory ignores the casino like nature of the foreign exchange markets and the ability of a country to undervalue its currency in world markets if left unchallenged to do so. (Bergsten) In the real world, a persistent deficit in a country's balance of trade is often far from ideal, and can have devastating consequences.

When the dollar is overvalued it causes domestic prices to be too high relative to foreign prices to achieve a balance in trade. The result is an increasing deficit in its balance of trade as imports grow more rapidly than exports. This kind of trade imbalance places pressure on wages and prices in the domestic economy as the under pricing of foreign goods threatens domestic producers with unfair competition from abroad. (Autor)

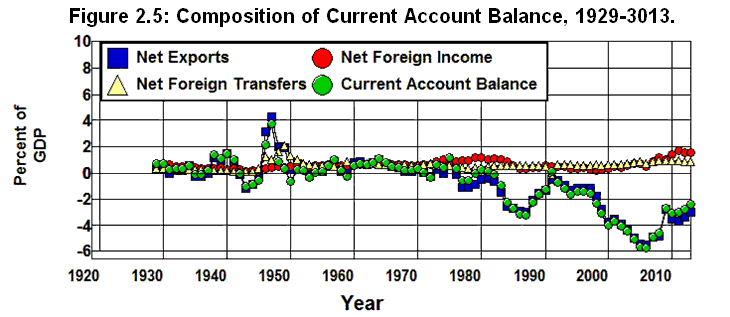

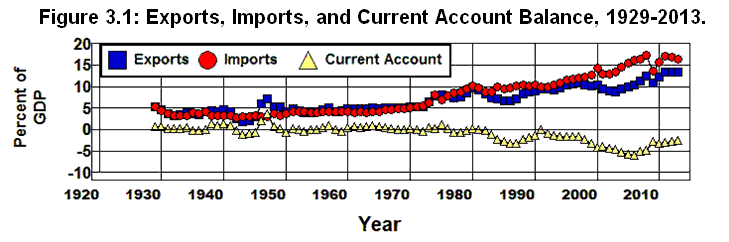

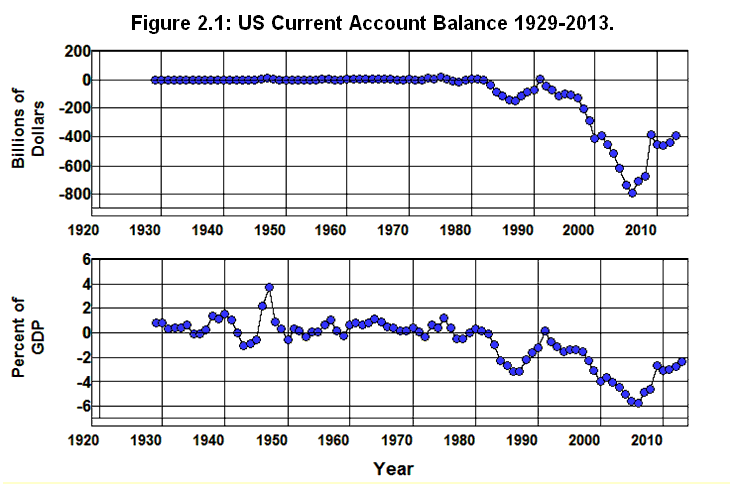

The extent to which our trade policies have allowed this to happen is indicated in Figure 2.1, which show our international current account balance from 1946 through 2008, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP. The current account balance is determined primarily by the difference between the value of our exports and the value of our imports. As is explained in the Appendix at the end of this chapter, it also includes net foreign transfers and the difference between income earned by Americans on foreign investments and income earned on domestic investments by foreigners, though these components of the current account balance are generally quite small compared to the values of exports and imports.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2013 (B103PDF|XLS), Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.2.5).

The graphs in this figure clearly show the consequences of our international policies as we went from a relatively stable balance through 1980 to a $160 billion deficit in 1987 that amounted to 3.4% of GDP. This balance gradually adjusted through 1991 then fell precipitously to reach a record deficit of $804 billion in 2006, a deficit equal to 6.0% of GDP.

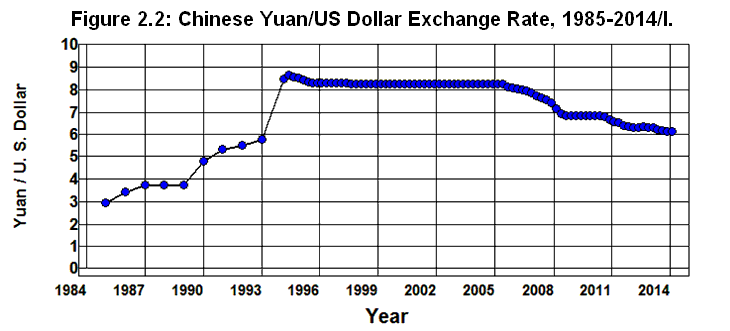

International exchange rates are supposed to adjust to eliminate this kind of imbalance, as they seemed to have in the 1980s, but, as was noted above, this will occur only if a country is not allowed to undervalue its currency in world markets over time. Figure 2.2 shows the Chinese yuan/dollar exchange rate from 1988 through the first quarter of 2014. Here is a classic example of how unregulated foreign exchange markets can fail to adjust as they are supposed to. Even though the trade deficit with China grew from $68.8 billion in 1999 to $372.7 billion through 2005, there was virtually no change in the yuan/dollar exchange rate in spite of this increase.

Source: Economic Report of the President: 2006 (B110PDF|XLS) OANDA .

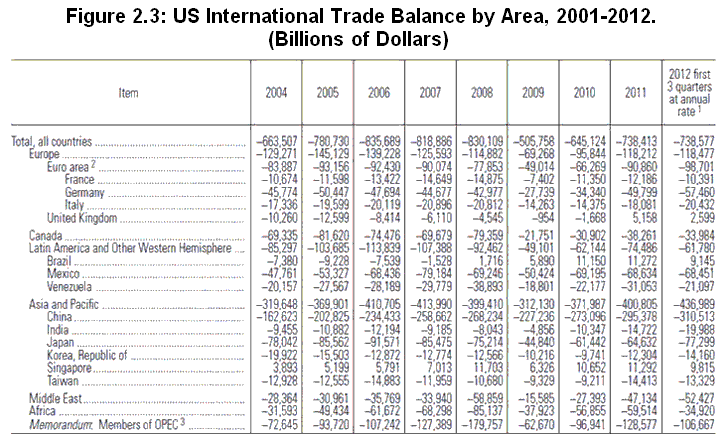

It is worth emphasizing at this point that even though our trade deficit with China is three times that of our deficit with the rest of Asia, all of Europe, or with Latin America, the problem is not just with the yuan/dollar exchange rate. As should be clear from Figure 2.3, the entire structure of US exchange rates is overvalued today. The table in this figure shows the US balance of trade with its major trading partners and with the major trading areas of the world from 2001 through the third quarter of 2009. A clear indication of the degree to which the entire structure of US exchange rates is too high is given by the fact that the only entity in this table with which the United States has not had a consistent negative balance over this nine years is Singapore.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2013 (B105PDF-XLS).

Undoubtedly, some of the deficits exhibited in this table can be explained by the growing need for U.S. dollars as international reserves held by foreign countries, but certainly not all. This situation is unsustainable, and the exchange markets will eventually adjust to correct this imbalance, but when this kind of imbalance is allowed to persist for any length of time, the eventual adjustment has the potential to precipitate a crisis that can lead to an economic disaster—a disaster that could have been avoided had this kind of imbalance not been allowed to occur in the first place. (Stiglitz Galbraith Reinhart Eichengreen Rodrik Bergsten)

Even more important is the fact that the persistence of this kind of imbalance has terribly destructive effects on our economy. The result of the unfair competition created by the overvalued US dollar has been the destruction of entire industries in the United States as much of the manufacturing sector of our economy has been outsourced to foreign lands. Particularly hard hit in this regard are the computer and consumer electronics industries. Equally disturbing is the fact that the technologies necessary to produce these goods have been shipped abroad as well. These technologies are essential to the increases in productivity necessary to improving our economic well being, but once the industries that embody these technologies are gone, they may be gone for a very long time. Even if the value of the dollar were to fall in the near future, it would take years to reconstitute many of these industries and to embed in the American economy the requisite capital and technologies needed to produce these goods. (Phillips Eichengreen Rodrik Palley)

The Overvalued Dollar and International Debt

The trade deficits cause by an overvalued dollar have another disturbing consequence. When we have a deficit in our balance of trade, the demand for dollars in the exchange markets to finance our exports is less than the supply of dollars made available in these markets through the purchase of our imports. This difference shows up as a deficit in our current account.[2.2] When such a deficit exists, foreigners end up accumulating more dollars than they need to purchase the amount of our exports they are willing to purchase at existing exchange rates.

At this point, foreigners have a choice: They can either refuse to accept more dollars at the existing exchange rates and, thereby, force our exchange rates down—thus, stimulating our exports and inhibiting our imports until a current account balance is obtained at a lower exchange rate—or they can use the excess dollars they are accumulating to purchase assets from Americans in the international capital markets. The assets purchased are essentially any asset an American is willing to sell for dollars but primarily consist of financial assets such as government and corporate securities.

The balance in the international capital market is referred to as our capital account balance, and this balance must, by definition, exactly offset our current account balance—that is, a deficit in our current account must, by definition, be offset by a surplus in our capital account that is exactly equal to the deficit in our current account. (Ott B103PDF-XLS)

When foreigners buy American assets in the international capital market, they are, in effect, investing in the United States. At the same time, to the extent these assets are government and corporate bonds, they are lending us money. To the extent these assets are not government and corporate bonds they must be corporate stocks, American businesses, real estate, or other nonfinancial assets in the United States. This means that the greater our current account deficit, the grater our capital account surplus must be, and, as a result, the current account deficits displayed in Figure 2.1 above indicate the rate at which we were driving ourselves into debt or selling our companies and other assets off to foreigners.

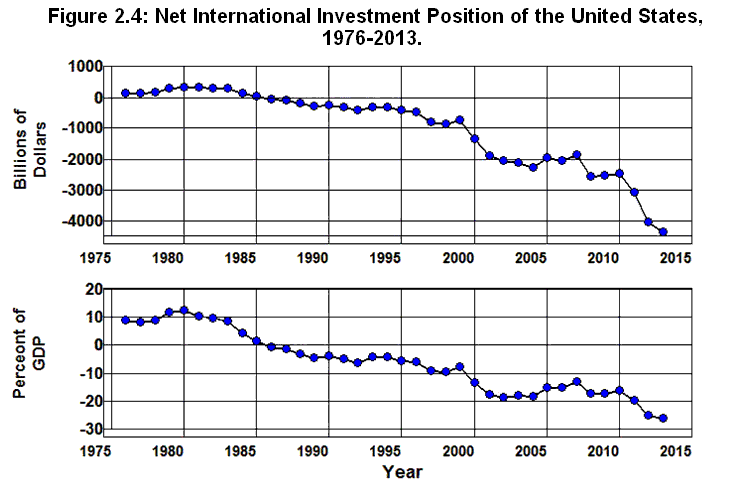

Figure 2.4 shows the Net International Investment Position of the United States from 1976 through 2013, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP, where Net International Investment is the difference between the value of the assets Americans own in foreign lands and the value of the assets foreigners own in the United States. It shows how the surpluses in our capital account that correspond to the deficits in our current account have accumulated. The extent to which this difference is made up of debt obligations—mostly corporate and government bonds—represents the net debt Americans owe to foreigners.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis ( 1.2.5). (1)